App Startup Time: Past, Present, and Future

Description: Learn about the dyld dynamic linker used on Apple platforms, how it's changed over the years, and where it's headed next. Find out how improved tooling makes it easier to optimize your app's launch time, and see how new changes coming in dyld will bring even further launch time improvements.

Terminology

- Startup time (for the scope of this talk): time spent before the app

main()is executed - Launch Closure: all of the information necessary to launch an application (e.g., what dylibs the app uses, what the offsets in them are for various symbols, where their code signatures are).

Tips

- Embed fewer dylibs

- Declare fewer classes/methods

- Use fewer initializers

- Use more Swift

- Swift avoids a lot of pitfalls that C, C++ and Objective-C allow you to do.

- Swift does not have initializers.

- Swift does not allow certain types of misaligned data structures that cost us time in launch

New tools to help find slow initializers

Use the Static Initializer tracer in instruments to profile your startup time:

- initializers are code that have to run before

mainto set up objects for your app - new in iOS 11 and macOS High Sierra

- provides precise timing for each static initializer

- works across multiple dylibs, including system dylibs that may be taking a long time because of inputs you've given them, such as complicated nibs

Dynamic Linking Through the Ages

Originally dyld did not have version numbers, but Apple is retroactively giving them.

dyld 1.0 (1996–2004)

- Shipped in NeXTStep 3.3

- before dyld, NeXT used static binaries

- Predated POSIX

dlopen()standardizeddlopenalready existed on some Unix systems, but were proprietary extensions- NeXTStep had different proprietary extensions

- Released before most systems used large C++ dynamic libraries

- C++ has a number of features, such as how its initializer ordering works. And one definition rule

- worked well in a static environment

- did not work with good performance in a dynamic environment

- large C++ code bases cause the dynamic linker to have to do a lot of work and it was quite slow

- Prebinding added in macOS Cheetah (10.0)

- technology where macOS would try to find fixed addresses for every dylib in the system and for your application, and the dynamic loader would try to load everything at those addresses and if it succeeded, it would edit all of those binaries to have those precalculated addresses in it, and then the next time when it put them in the same addresses, it didn't have to do any additional work

- pro: prebinding sped up launch a lot

- cons: prebinding was editing your binaries on every launch

dyld 2.0 (2004–2007)

- Shipped in macOS Tiger

- Complete rewrite

- Correct C++ initializer semantics (extended the mach-o format and updated dyld so that we could get efficient C++ library support)

- Full native

dlopen()/dlsym()semantics (deprecated legacy proprietary APIs)

- Designed for speed

- Limited sanity checking

- It had security issues for speed's sake (Apple went back and fix some of those)

- Reduced prebinding

- only edited the system library addresses

- if you've ever seen the phrase

optimizing system performanceappear in your software update, that was added to the installer to be displayed during the time the system was updating prebinding (nowadays the message is used for all sort of optimizations)

dyld 2.x (2007–2017)

Many minor updates along the way:

- More architectures support: x86, x86_64, arm, arm64

- More platforms support: iOS, tvOS, watchOS

- Improved security

- Codesigning support

- ASLR (Address Space Layout Randomization), which means that every time you loaded any library, they may be at a different address

- bounds checking to a number of parts of the mach-o header (to void certain types of attach with malformed binaries)

- Improved performance

- Prebinding completely replaced by Shared Cache

Shared Cache

- Introduced in iOS 3.1 and macOS Snow Leopard

- It's a single file that contains most system dylibs

- since it's just a single file, the system can do certain types of optimizations:

- Rearranges binaries to improve load speed Pre-links dylibs (e.g. rearrange all of their text segments and all of their data segments and rewrite their entire symbol tables to reduce the size and to make it so we need to mount fewer regions in each process. It also allows us to pack binary segments and save a lot of RAM)

- pre-links dylibs (on an average iOS system, this is the difference in about 500MB to 1GB of RAM at runtime)

- pre-builds data structures used by dyld and ObjC (so we don't have to do it on launch, saves both ram and time)

- since it's just a single file, the system can do certain types of optimizations:

- Built locally on macOS (when you see

optimizing system performance, the system is running an update on the dyld shared cache) - Build at Apple and shipped with OS updates for all other Apple OS platforms

dyld 3 (2017)

- Announced today

- Complete rethink of dynamic linking

- Will be on be the default for system apps for 2017 Apple OS platforms

- Will completely replace dyld 2.x on Apple OS platforms (for all third-party apps as well)

- Fully compatible with dyld 2.x

Key points:

- performance

- security

- testability/reliability

Changes:

- Move complex operations out of process (most of

dyldis now a regular daemon)- the remaining bit of

dyldthat stays in process is as small as possible, thus reducing the attack surface in your applications - speeds up launch

- the remaining bit of

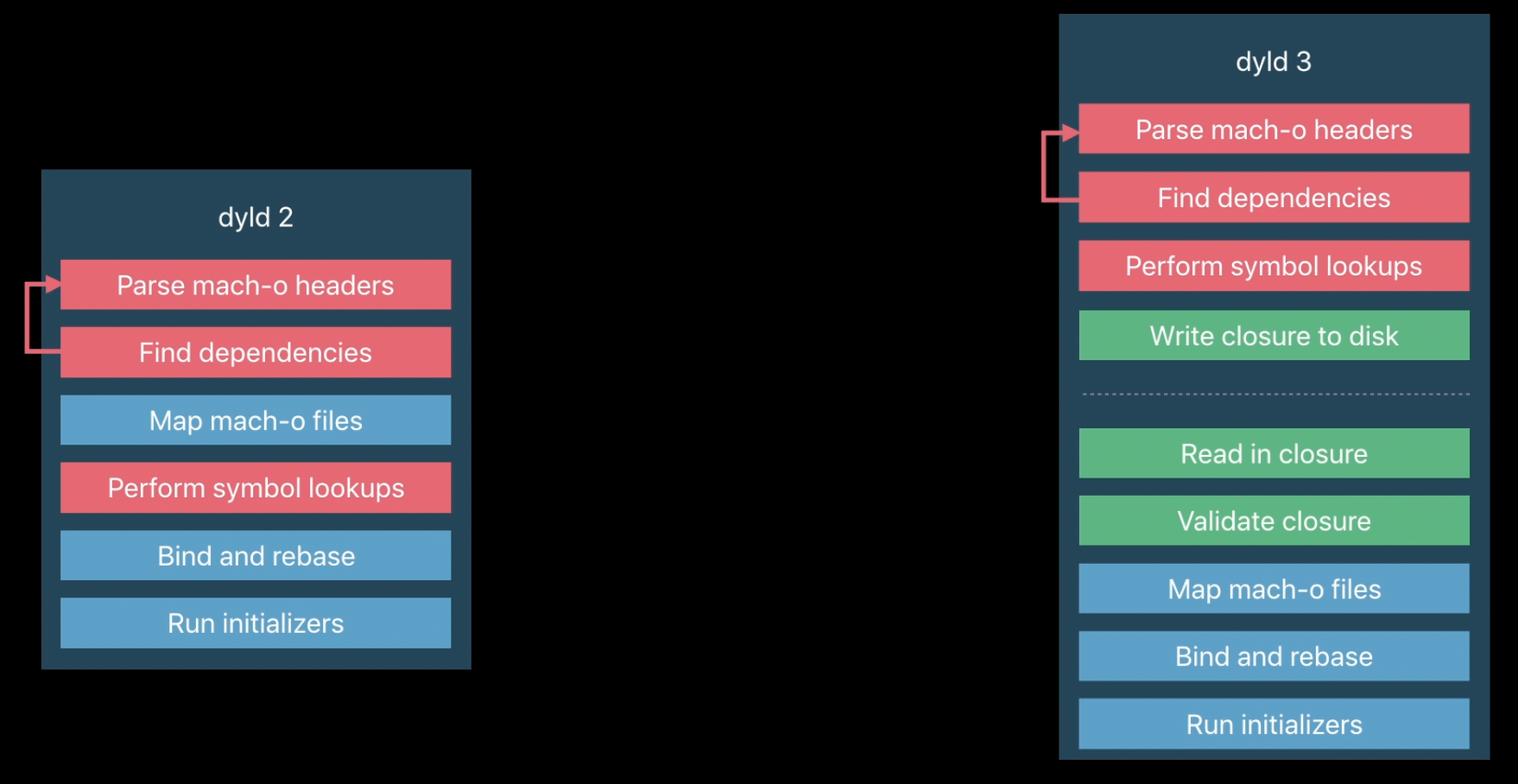

How dyld 2 and dyld 3 launch an app

dyld 2

- parse app mach-o header

- find all dependencies/libraries (parse those library mach-o headers, repeat if those libraries depend on other libraries)

- repeat steps above until we have a complete graph of all your dylibs

- map mach-o files (so the system gets all libraries into your app address space)

- perform symbol lookups (for each API the app uses, the system essentially copies that into a function pointer in your application)

- bind and rebase (ASLR)

- run initializers

- call your app main

dyld 3

dyld has three components:

- out of process mach-o parser and compiler

- parses the app mach-o headers and solve all app dependencies

- performs symbols lookups

- the outcome is then cached in a closure to disk

- this is possible because:

- dependencies don't change between launches

- symbol locations within a mach-o do not change between launches

- in-process engine that runs launch closure

- launch closure caching service

Most launches use the cache and never invoke the out-of-process mach-o parser/compiler

The typical launch becomes:

- read in closure

- validate closure

- map mach-o files (so the system gets all libraries into your app address space)

- bind and rebase (ASLR)

- run initializers

- call your app main

dyld 3 architecture

Three components:

- Out of process mach-o parser and compiler

- Small in-process engine

- Launch closure caching service

Out of process mach-o parser

Is a normal daemon that can use normal testing infrastructure.

- Resolves all search paths, @rpaths, environment variables

- Parses the mach-o binaries

- Performs all symbol lookups

- Creates a launch closure with results

Small in-process engine

This is the part that runs in the app process.

- Validates launch closure

- Maps in all dylibs

- Applies fixups

- Runs initializers

- Jumps to

main()

It never needs to parse mach-o headers or access the symbol tables

Launch closure caching service

- System app launch closures built into shared cache

- Third-party app launch closures built during install

- Rebuilt during software update (by default these will all be prebuilt for you on iOS and tvOS and watchOS before you even run)

- On macOS the in-process engine can call out to a daemon if necessary

- on first launch and/or after an OS update

- necessary because of app side loading

- Not necessary on other Apple OS platforms

GitHub

GitHub

zntfdr.dev

zntfdr.dev