Protocol and Value Oriented Programming in UIKit Apps

Description: Building on last year's Protocol-Oriented Programming and Building Better Apps with Value Types sessions, this year's session will highlight tips and tricks for building better Swift apps. See how you can incorporate these design approaches into a real MVC-based Cocoa Touch app, especially in the view and controller layers, where you might not have thought of using these techniques before.

Prerequisites

This session builds on the following 2 sessions from WWDC 2015:

Overview

This session is about using value types and protocols to make our apps better. A key component is local reasoning, which means that when we look at some code, we don't have to think about how the rest of our code interacts with that one function/class/etc.

Local reasoning makes our code easier to maintain, easier to write, and easier to test. We're focused on local reasoning in the context of Model-View-Controller (MVC) apps. In MVC:

- The Model stores our data

- The View presents our data

- The Controller coordinates between the model and view

Lucid Dreams

Our example app is Lucid Dreams, which lets people record their dreams so they can remember them later.

When we open the app, we immediately see a list of dreams that we've had:

Tapping a dream allows us to edit it:

Roadmap

- Recap of value types and protocols in the Model layer (this was mostly covered in the prerequisite sessions)

- View layer

- Controller layer

The sample code for Lucid Dreams is available at this link.

1. Model

What is a dream?

We need to represent dream entries in our application.

// Reference semantics

class Dream {

var description: String

var creature: Creature

var effects: Set<Effect>

// ...

}

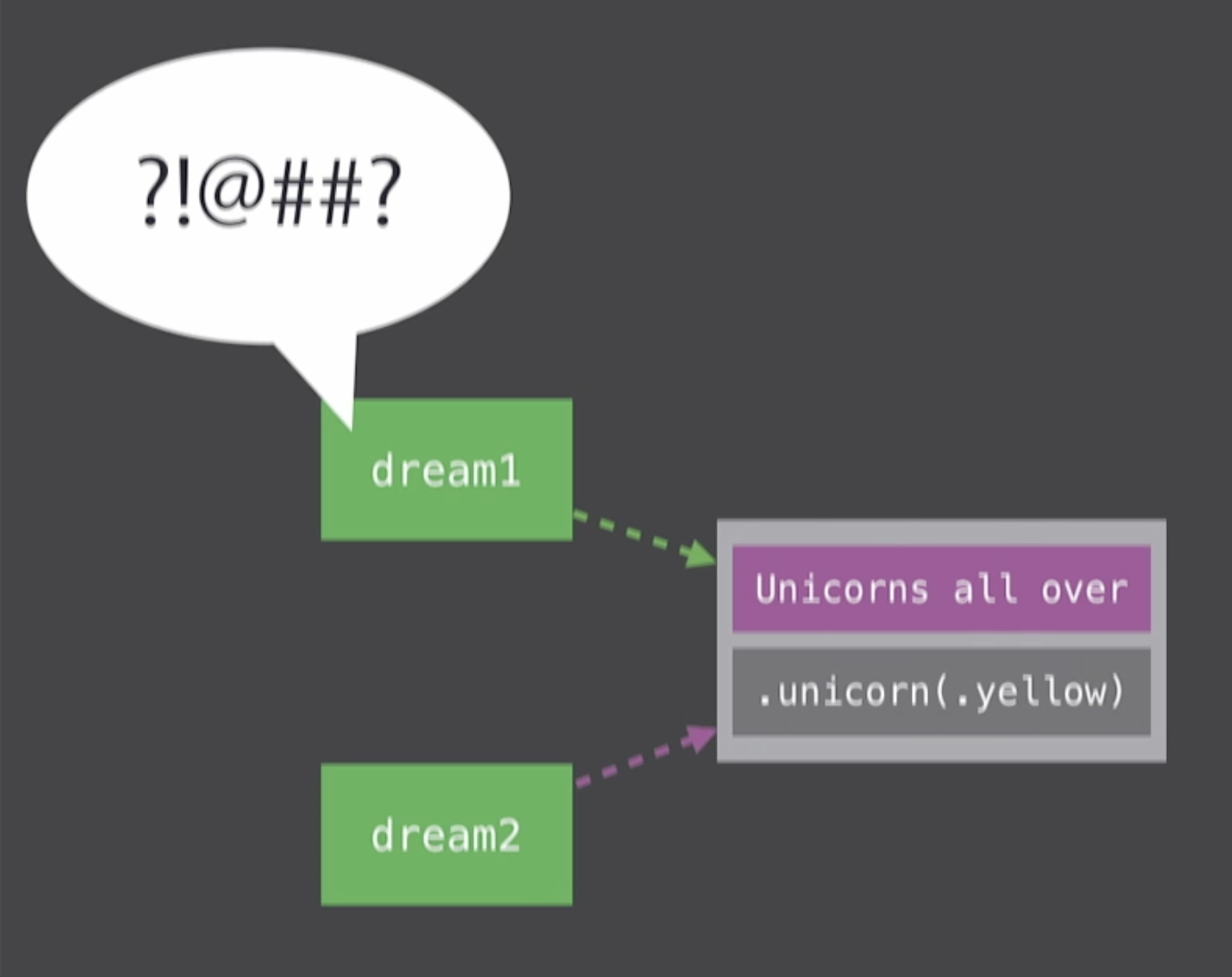

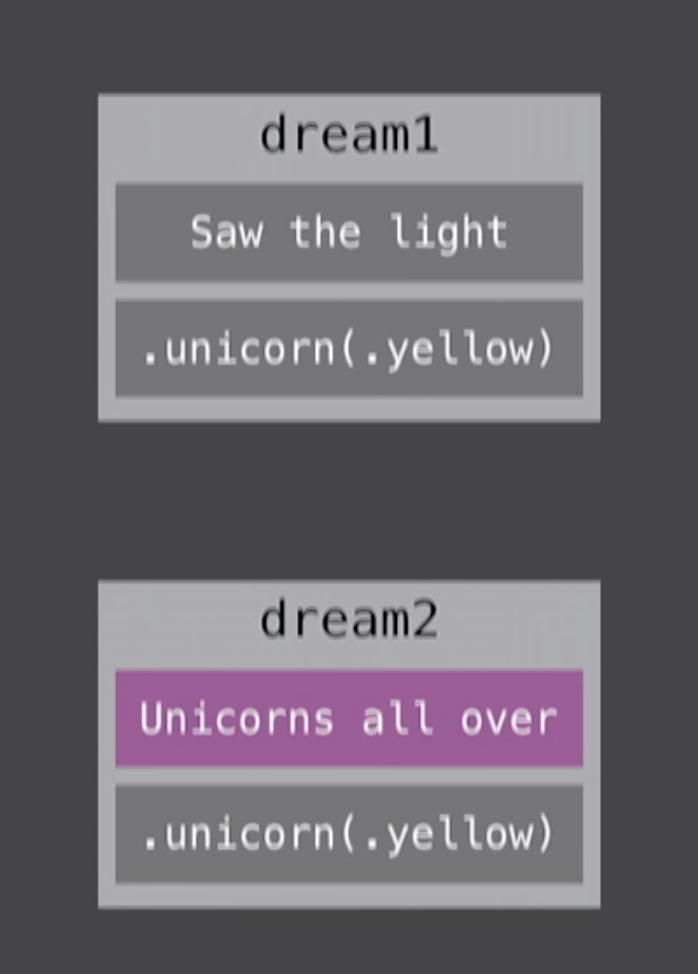

Classes use reference semantics, meaning that references to the same object share their storage. This can be a problem if dream1 isn't expecting its description to be changed:

var dream1 = Dream(...)

var dream2 = dream1

dream2.description = "Unicorns all over" // Changed for dream1 AND dream2!

Unintended mutations hurt local reasoning.

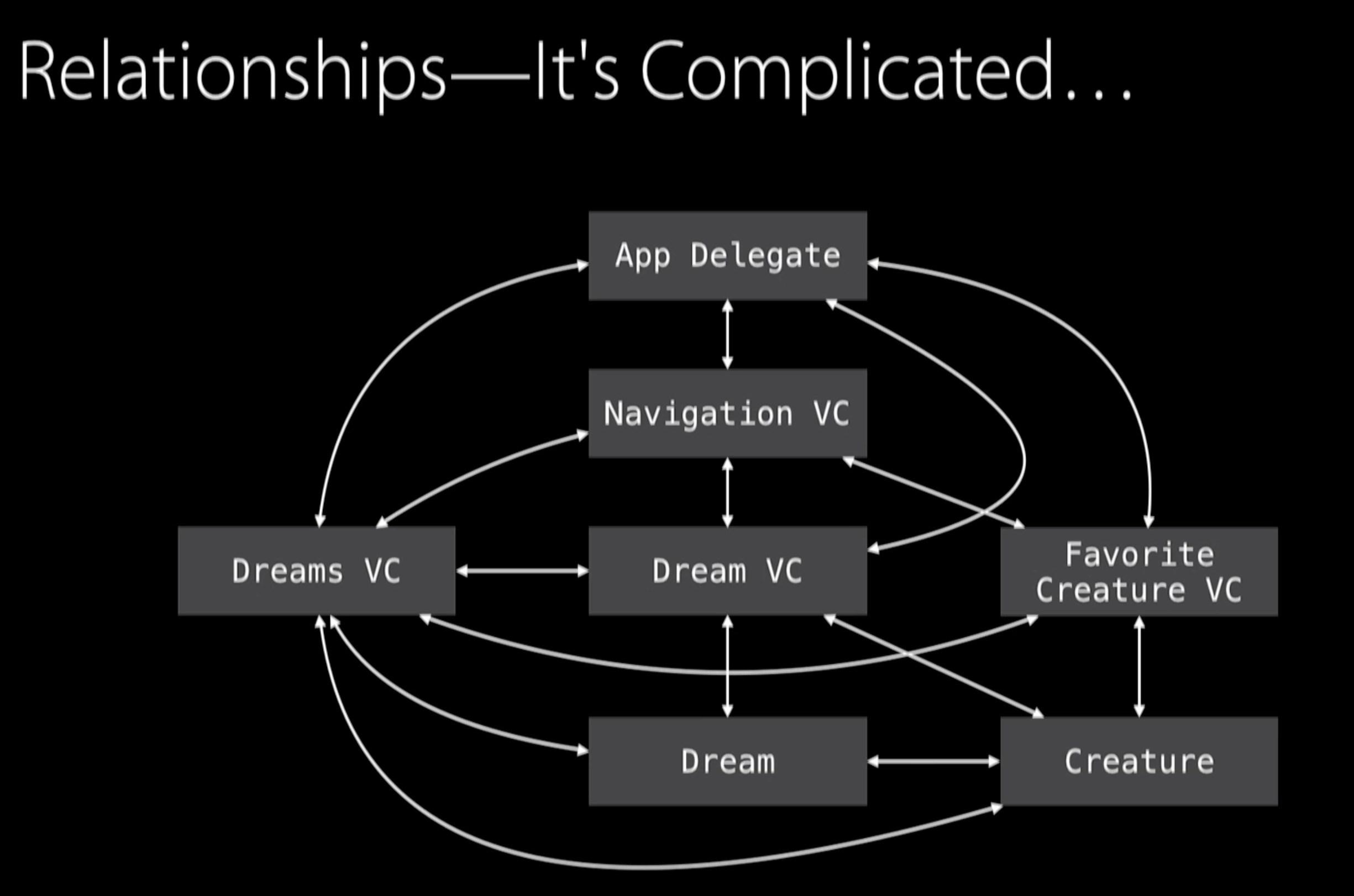

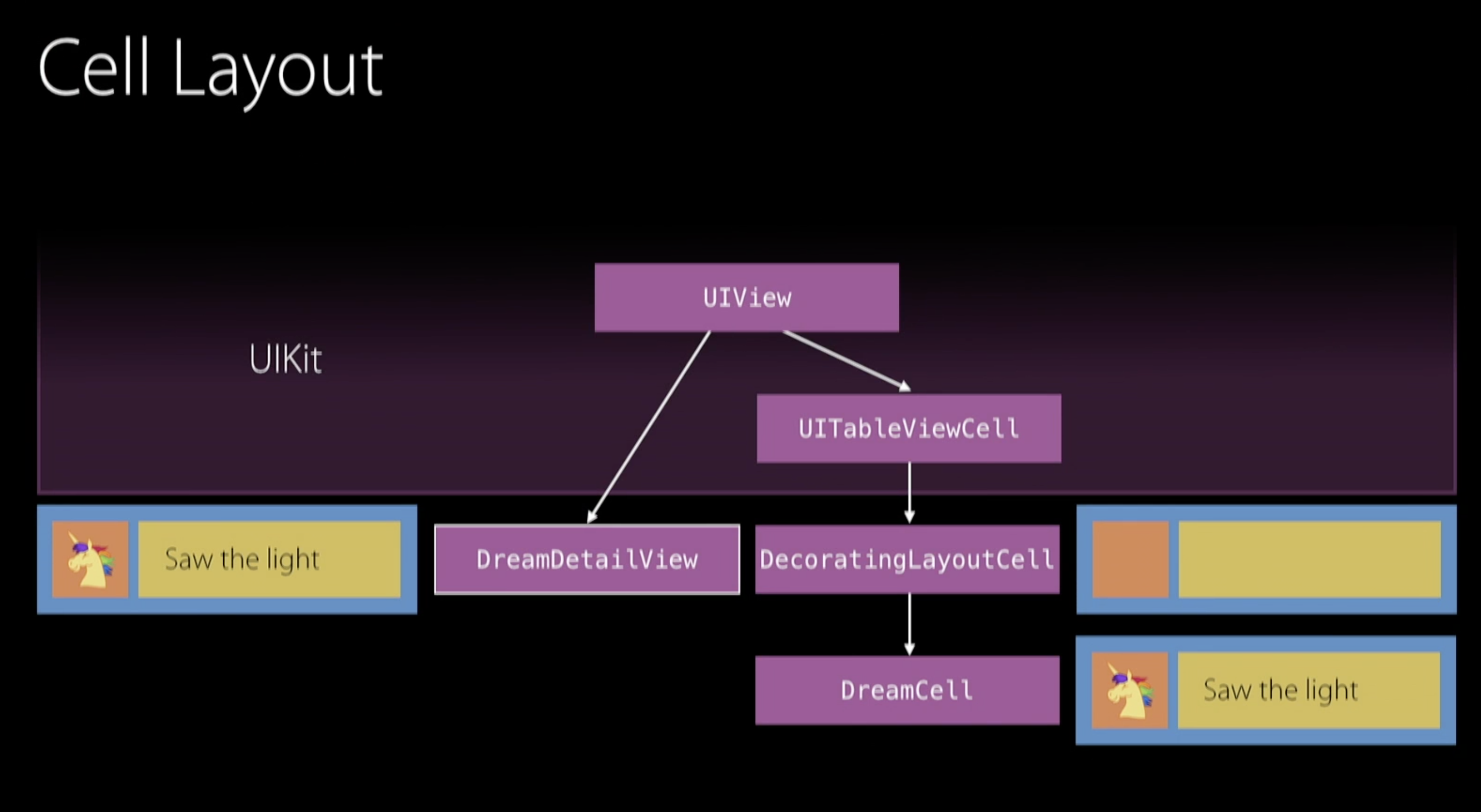

This diagram shows relationships between entities in an early version of Lucid Dreams. Relationships can be explicit, implicit, one-way, two-way, dynamic, or static:

What happens if we test the Dream type on its own? Even if we create a dream that stands by itself, we won't be testing its real usage because there are many more dependencies that we're not considering. Our tests may pass, but real usage may introduce unintentional mutations.

We can solve this ambiguity by making our Dream type a struct, which has value semantics. This means each variable has independent storage--changing the value of one doesn't affect another. This also means that Dreams aren't involved in the complicated relationships we saw earlier.

Using value semantics improves our ability to reason locally. We should use value semantics beyond just the model layer!

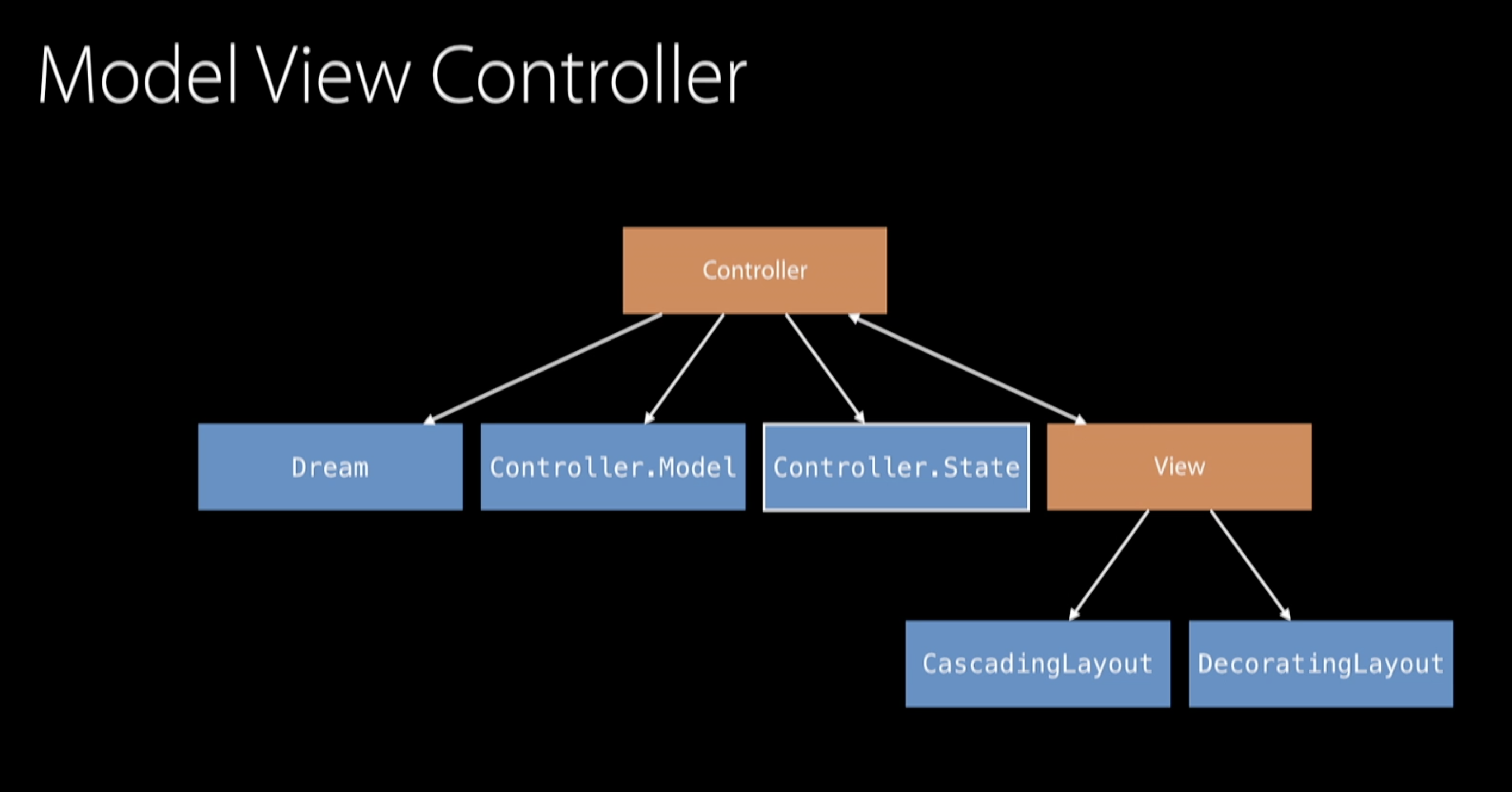

2. View layer (cell layout)

An earlier version of Lucid Dreams created cells as abstract subclasses of UITableViewCell. For example, DecoratingLayoutCell shows a decoration on the left and a larger content area on the right.

Then, the team made a concrete subclass of the layout cell called DreamCell, which shows a dream image and description.

The team used this architecture because they wanted to be able to use their layout in different places. Unfortunately, this didn't work out; it was easy to use inside table views, but hard to use in any other type of view.

The team wanted to find a better architecture where they could use their layouts together with table view cells and plain UIViews. They also wanted to add SpriteKit to show particle effects.

Note: while this example focuses on layout, the strategies discussed can be used in any part of an app.

Refactoring our cell

Before:

class DecoratingLayoutCell: UITableViewCell {

var content: UIView

var decoration: UIView

// Perform layout

}

There's no need for layout logic to be trapped inside of a cell; it's just math and geometry to figure out the size of some frames. Let's change this to a struct that asks for a rectangle when performing layout.

struct DecoratingLayout {

var content: UIView

var decoration: UIView

mutating func layout(in rect: CGRect) {

// Perform layout

}

}

With this small change, we now have an isolated piece of code that only knows how to do layout. We can update our DreamCell to use this new struct to lay out its children.

class DreamCell: UITableViewCell {

// ...

override func layoutSubviews() {

var decoratingLayout = DecoratingLayout(content: content, decoration: decoration)

decoratingLayout.layout(in: bounds)

}

}

We can also use this exact same code in our UIView subclass because the layout logic is decoupled from table view cells.

class DreamDetailView: UIView {

// ...

override func layoutSubviews() {

var decoratingLayout = DecoratingLayout(content: content, decoration: decoration)

decoratingLayout.layout(in: bounds)

}

}

Testing

Now that our layout can be used in isolation, it's really easy for us to write a unit test. We just create some views, add them to our layout, and then lay them out in a known rect. Then, we just have to verify that the resulting frames are what we expected.

func testLayout() {

let child1 = UIView()

let child2 = UIView()

var decoratingLayout = DecoratingLayout(content: content, decoration: decoration)

decoratingLayout.layout(in: CGRect(x: 0, y: 0, width: 120, height: 40))

XCTAssertEqual(child1.frame, CGRect(x: 0, y: 5, width: 35, height: 30))

XCTAssertEqual(child2.frame, CGRect(x: 35, y: 5, width: 70, height: 30))

}

Our test doesn't have to create a table view or wait for the right view layout callbacks to happen. It can just tell our layout to work and then verify the output.

This is a general benefit we have now: our new layout struct is really small and focused, so it's easy to reason locally about this code. We only have to understand the struct in isolation.

Supporting SpriteKit

We don't want to have to duplicate our DecoratingLayout code into something like this:

// We DON'T want this.

struct ViewDecoratingLayout {

var content: UIView

var decoration: UIView

mutating func layout(in rect: CGRect) {

content.frame = ...

decoration.frame = ...

}

}

struct NodeDecoratingLayout {

var content: SKNode

var decoration: SKNode

mutating func layout(in rect: CGRect) {

content.frame = ...

decoration.frame = ...

}

}

SKNode is not a subclass of UIView, so there's no common superclass that we can use here. How can we combine these together into a single layout?

The only operations we perform with content and decoration is to set their frames, so that's the only functionality we need to mandate. We can represent that requirement with a protocol and eliminate duplicate code.

protocol Layout {

var frame: CGRect { get set }

}

struct DecoratingLayout {

var content: Layout

var decoration: Layout

mutating func layout(in rect: CGRect) {

content.frame = ...

decoration.frame = ...

}

}

Finally, we can use retroactive modeling to make UIView and SKNode conform to our new protocol.

extension UIView: Layout {}

extension SKNode: Layout {}

This is one of the benefits of relying on protocols instead of superclasses for polymorphism. We can add functionality to unrelated types within a specific context.

Another benefit is that our DecoratingLayout no longer needs a dependency on UIKit or SpriteKit, so we can easily bring the same system to AppKit to support layouts on NSViews.

Generic types

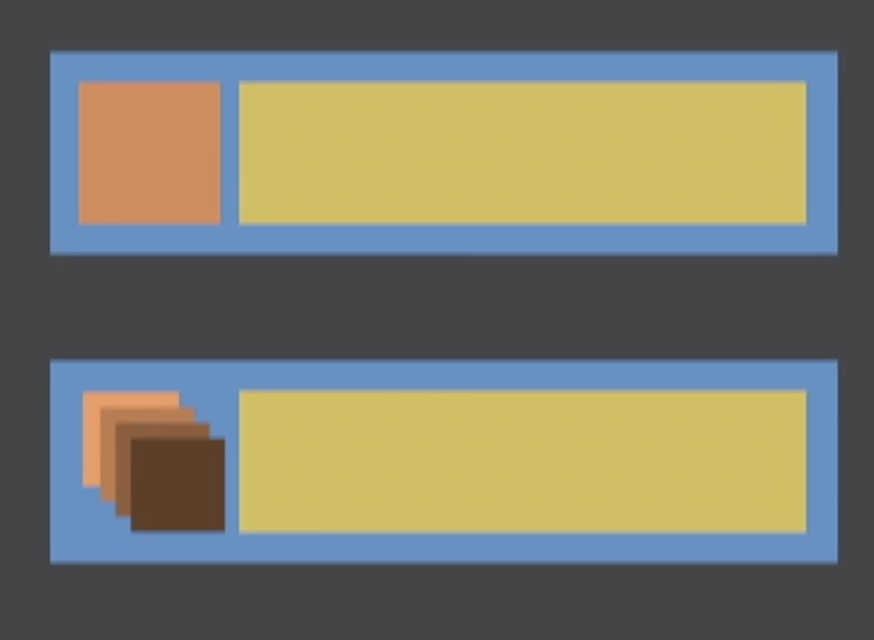

When we're using DecoratingLayout in a view, we want to be able to add all of its content as subviews. Similarly, when we're using it in a SpriteKit scene, we want to be able to add our content as child nodes.

Right now, content and decoration can be any type that has a frame. This could mean that we could have content: UIView and decoration: SKNode in the same struct. We need to make our requirements more strict so that we have only UIView or only SKNode.

Swift lets us use generics to require that both content and decoration are the same concrete type:

struct DecoratingLayout<Child: Layout> {

var content: Child

var decoration: Child

mutating func layout(in rect: CGRect) { ... }

}

Generics are useful because:

- They give us more control over types

- They can be further optimized at compile time because the compiler has more information about what we're doing

To learn more, see Understanding Swift Performance.

Sharing code

We have a great implementation of DecoratingLayout, but our app also includes other types of layouts like a CascadingLayout. Both show decoration on the left and content on the right with some minor differences, so we should be able to reuse a lot of code.

Inheritance

One possible tool is inheritance, but that carries a lot of responsibility. We would have to consider what our superclass is doing, and what any subclasses may want to change or override. Also, we usually have to inherit from a framework class like UIView, and there's a lot more code to consider there.

In short, inheritance doesn't give us local reasoning.

Composition

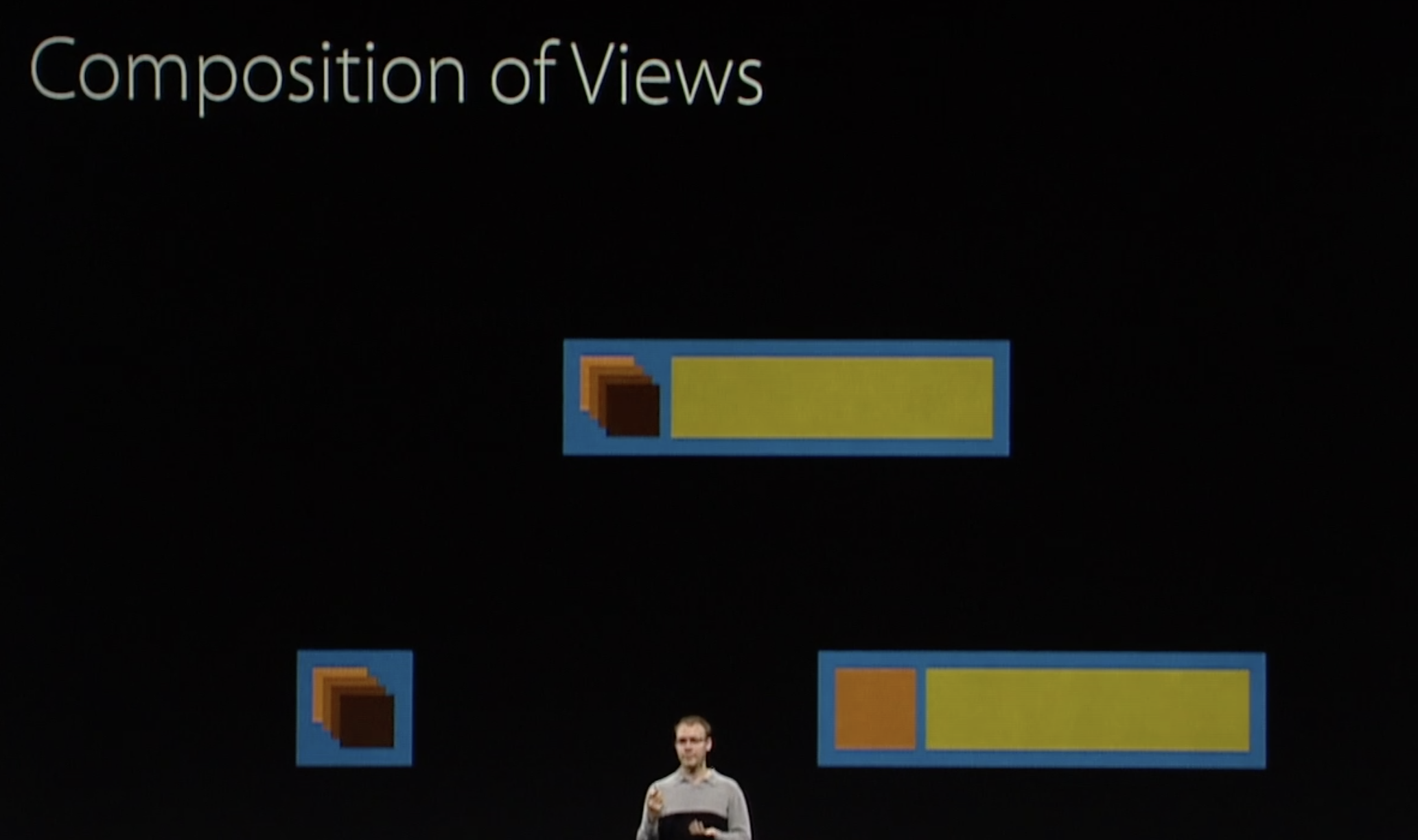

A better solution is composition, the idea of combining smaller pieces to build larger pieces. This allows us to understand each independent piece in isolation. We can also enforce encapsulation without worrying about subclasses or superclasses poking holes in our abstractions.

We could write CascadingLayout with a UIView that handles cascading and a DecoratingLayout that handles our decorating layout behavior. We could then add both of these as subviews in our UITableViewCell.

The problem is that class instances are expensive. Each new class instance requires an allocation on the heap. Views are even more expensive because there's a lot of work needed to support a view's drawing and event handling.

Making a view that does no drawing and only acts as a layout abstraction is very wasteful.

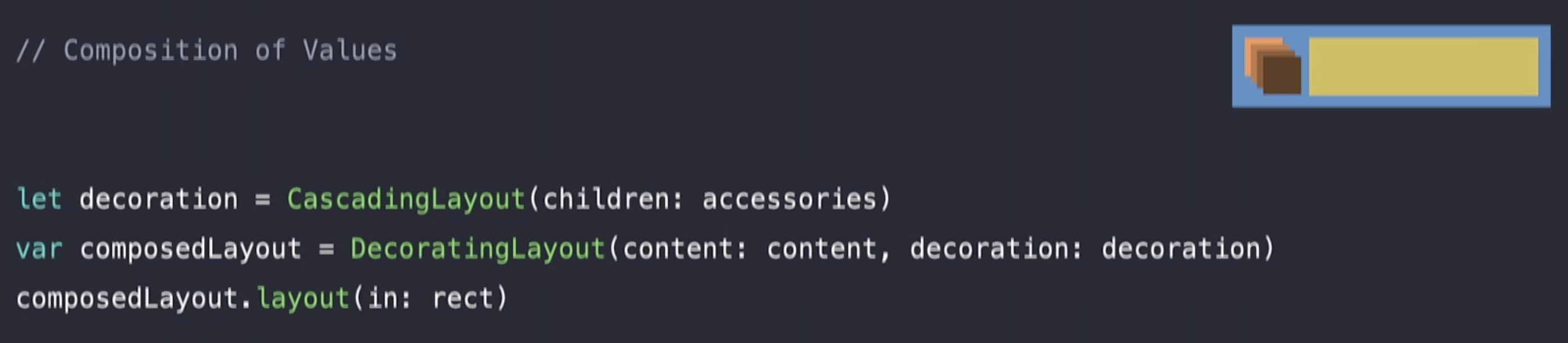

Composition of value types

The correct approach is to use composition, but with value types instead of views.

- Structs are very lightweight!

- Value semantics give us much better encapsulation, so we can put pieces together without worrying about someone else modifying the copy that we're using.

We can write the cascading part with an array of children that are laid out:

struct CascadingLayout<Child: Layout> {

var children: [Child]

mutating func layout(in rect: CGRect) {

...

}

}

Then, we can use DecoratingLayout to get the desired effect:

struct DecoratingLayout {

var content: Layout

var decoration: Layout

mutating func layout(in rect: CGRect) {

content.frame = ...

decoration.frame = ...

}

}

There's still one more problem: these layouts only expect to have children that are either UIViews or SKNodes. We should generalize this so we can use layouts and compose them together.

Currently, our Layout protocol requires a frame property, but we only ever set a frame. We don't actually care if child views have a frame or not. We just want to be able to tell a child view to lay itself out in a given rect.

Let's change our protocol to better reflect our intentions.

protocol Layout {

mutating func layout(in rect: CGRect)

}

UIView and SKNode can still conform to this protocol. When layout is called, they'll just set their frame.

But now, we can make our layouts conform to this protocol as well. They already know how to do layout! When given a frame, they just divide up that rect and pass it to their children.

struct DecoratingLayout<Child: Layout>: Layout { ... }

struct CascadingLayout<Child: Layout>: Layout { ... }

Now we can build a fancy layout by composing together a CascadingLayout and a DecoratingLayout.

Composition helps us build out layouts in a very declarative way. There's even more examples in the sample code.

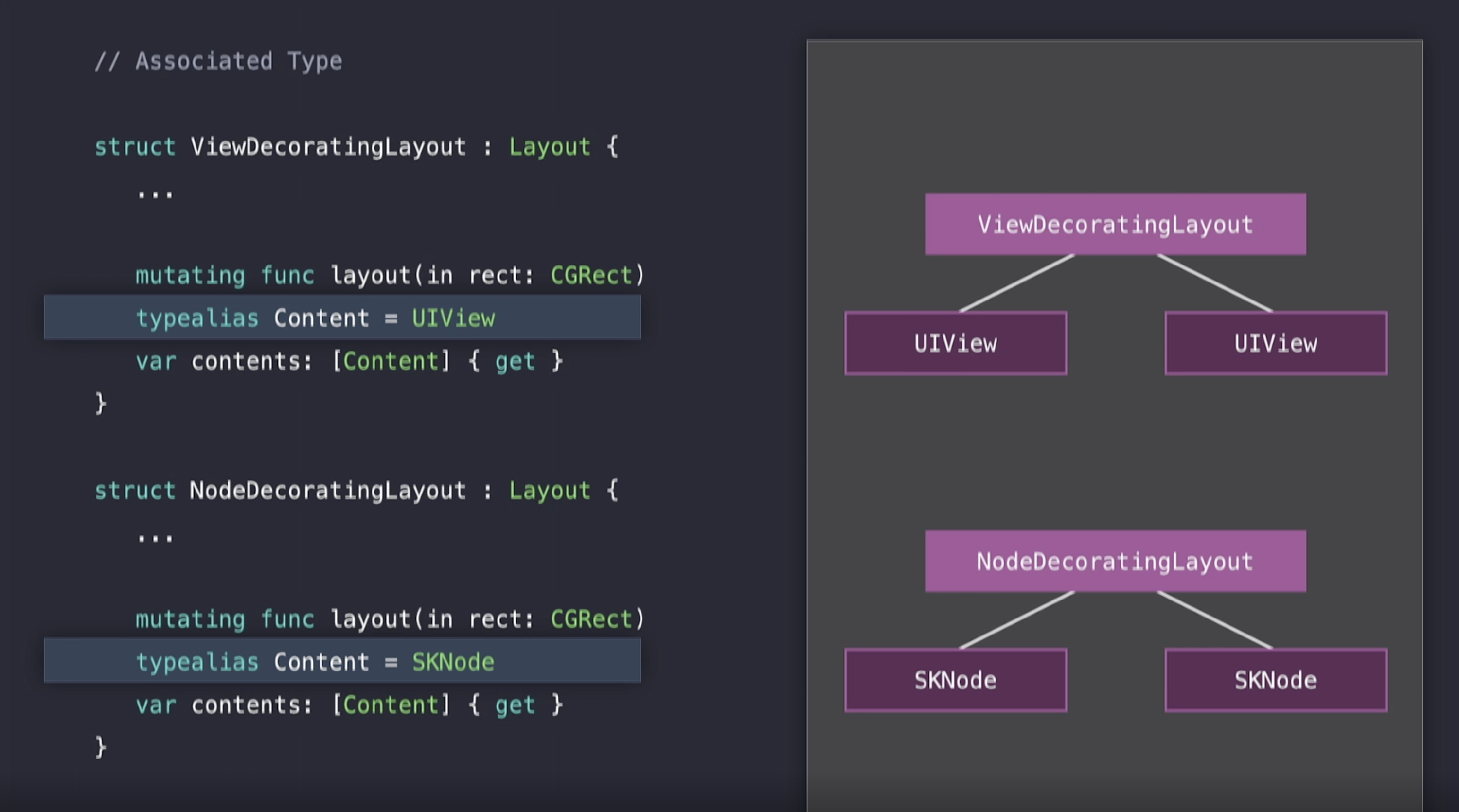

Associatedtypes

We want to be able to add the contents of our layout to either a superview or a SpriteKit scene. An important part of the functionality is adding contents in the right order. For example, our CascadingLayout wants its children to be ordered so that they line up on top of each other.

Let's expand our protocol to support that as well. We'll add a property to be able to return its contents, and our combining layouts will use this property to return all contents in the correct order. Leaf views and nodes can just return themselves.

protocol Layout {

mutating func layout(in rect: CGRect)

var contents: [Layout] { get }

}

If we have the type of contents match our protocol, then we would again be allowing mixed environments of UIViews and SKNodes. Since we're adding these children to a parent, we only want to allow a homogenous collection of just UIViews or just SKNodes.

To enforce this requirement, we can add an associated type to our protocol. An associated type is like a type placeholder. The conforming type chooses the concrete type that it wants to use.

protocol Layout {

mutating func layout(in rect: CGRect)

associatedtype Content

var contents: [Layout] { get }

}

This allows us to write something that just knows how to lay out views. Our Layout object can specify that its content type is either UIView or SKNode.

This type safety is great, but again, we don't want to have to write a separate layout for views and nodes. We can fix this by using a generic version of our layout, where our content type can be whatever the content of our child is.

This means we can make a DecoratingLayout that works only with UIViews or only with SKNodes. Both are strongly typed so that we can pull out their contents and know exactly what they are, and they can still share all of the layout logic.

struct DecoratingLayout<Child: Layout>: Layout {

// ...

mutating func layout(in rect: CGRect) { ... }

typealias Content = Child.Content

var contents: [Content] { get }

}

Associated types are a great way to make protocols even more powerful.

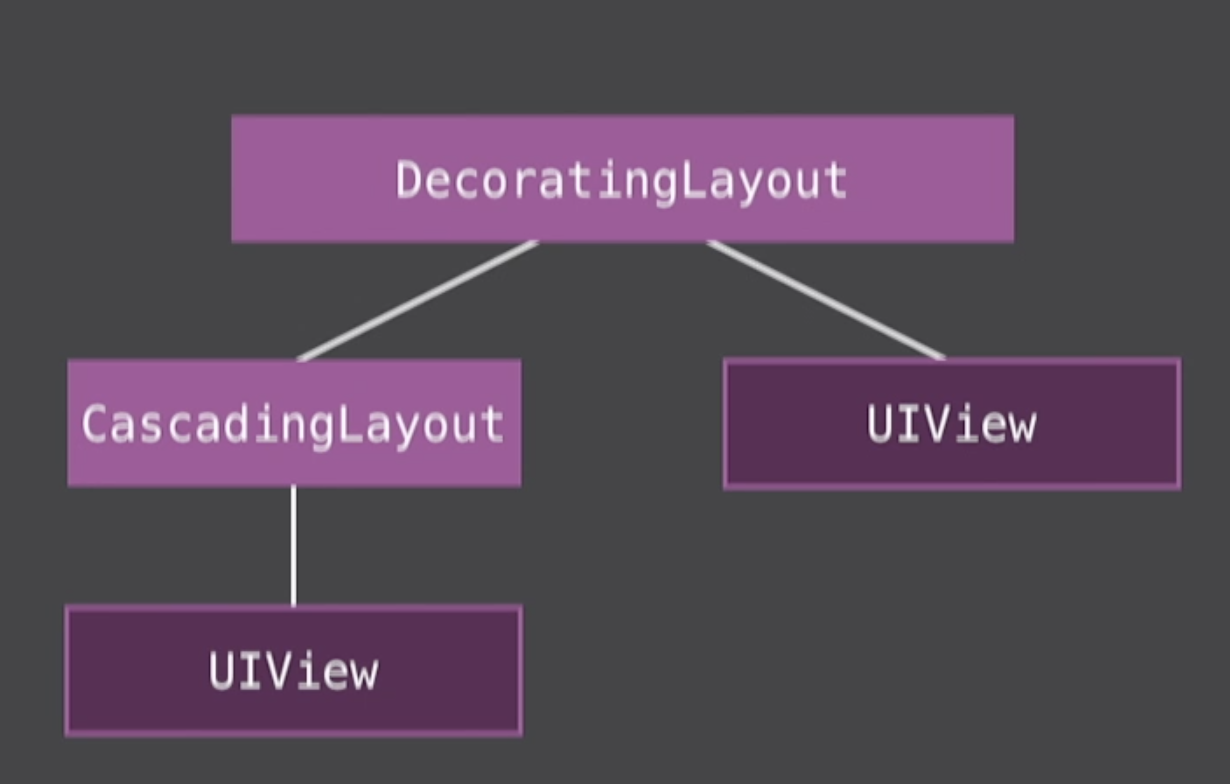

Heterogeneous layouts

Currently, we force our content and decoration views to be the same type, but this doesn't work if we want a CascadingLayout together with a UIView.

What we really want is for all our contents to have the same type. Let's update our layouts to reflect that.

We can use 2 generic type parameters, one for each child, and we can specify that only the contents have to be the same type:

struct DecoratingLayout<

Child: Layout, Decoration: Layout where Child.Content == Decoration.Content

>: Layout {

var content: Child

var decoration: Decoration

mutating func layout(in rect: CGRect) { ... }

typealias Content = Child.Content

var contents: [Content] { get }

}

Finished protocol

Here's our finished protocol, which represents exactly what it means to be part of the layout process. See the sample app for more examples of how this was used, such as rendering images on a background thread.

protocol Layout {

mutating func layout(in rect: CGRect)

associatedtype Content

var contents: [Content] { get }

}

Unit tests

One more place we can take advantage of this protocol is in our unit tests.

We can write a struct that has a frame property and conforms to our Layout protocol. Then, we can change our unit test to use this instead of UIViews as the children in our layout, which removes the dependency on UIKit.

struct TestLayout: Layout {

var frame: CGRect

// ...

}

func testLayout() {

let child1 = TestLayout()

let child2 = TestLayout()

// same assertions as before...

}

Our tests now only rely on the logic in our own layout and test structs. We're unit testing our layout without using the GUI.

General Swift techniques

- Improve local reasoning with value types

- Use generic types for fast, safe polymorphism

- Composition of values is a great way to customize/build complex behavior

3. Controller

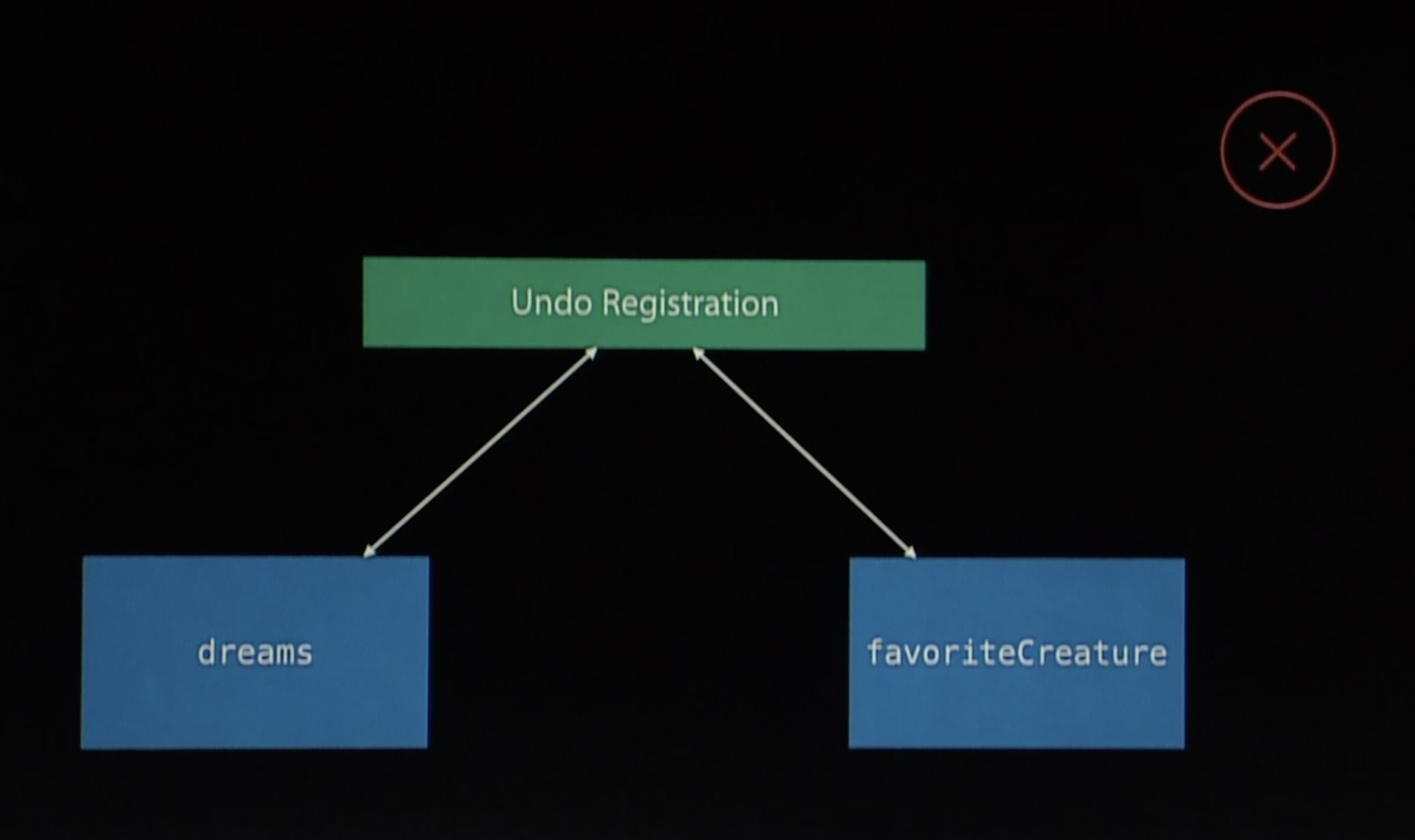

Undo bug

Shake-to-undo doesn't work when changing our Favorite Creature. Watch 25:00-25:35 for a demo of the bug.

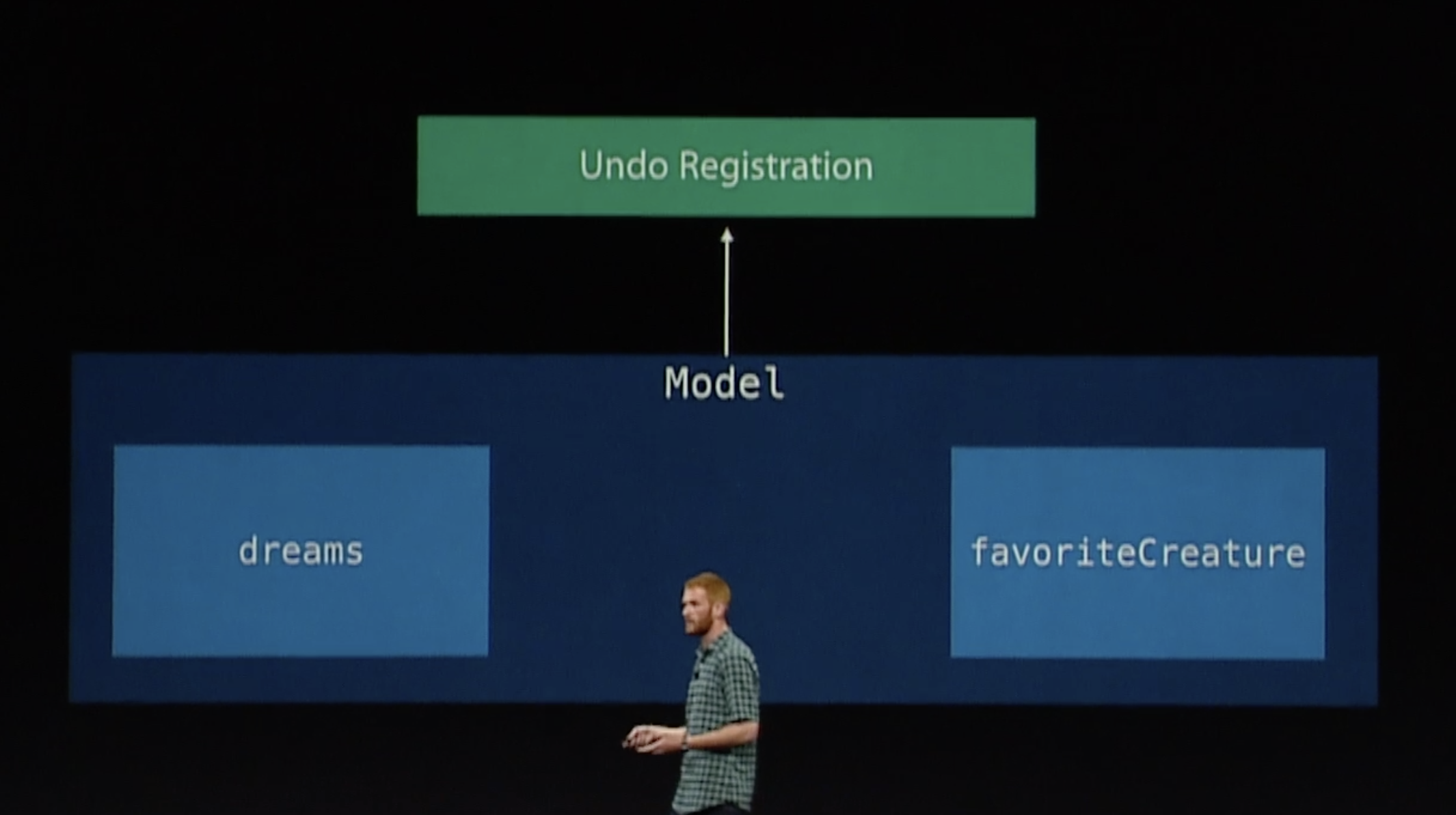

The DreamListViewController has 2 model properties: the favorite creature and the list of dreams:

class DreamListViewController: UITableViewController {

var favoriteCreature: Creature

var dreams: [Dream]

// ...

}

Our bug exists because the team forgot to add code to undo favoriteCreature. However, adding a new code path for every new model object can become a maintenance nightmare.

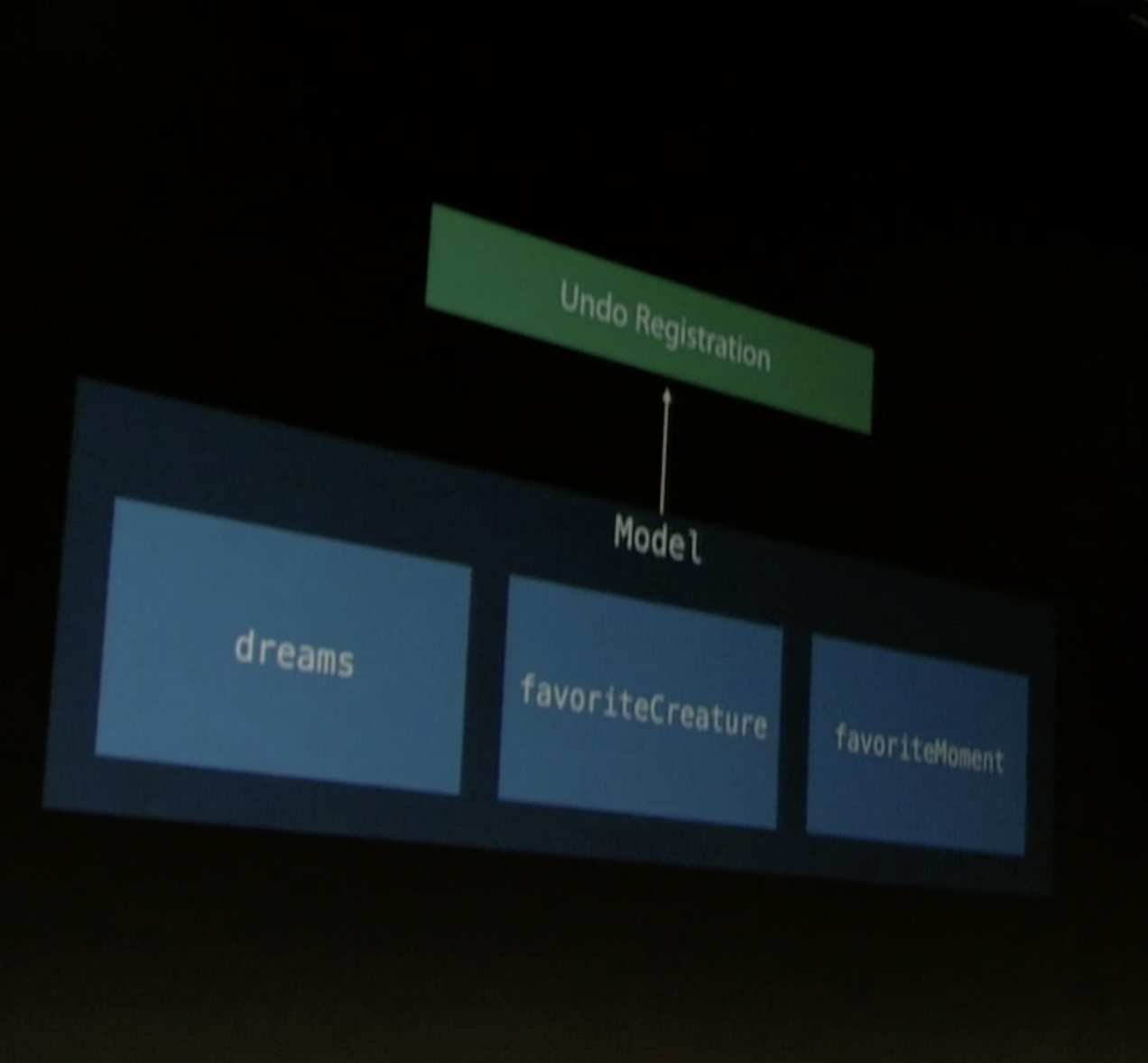

There's an approach that can scale better as we add more model properties: Composition! We can compose these model properties into a single Model struct, and our undo logic will work only with Model objects.

As discussed earlier, it's imperative that Model uses value semantics because it's composed of multiple other values.

Now, we can just keep adding objects to our single Model property and our undo functionality will work with no extra code.

Isolating the model

We can start by moving our model properties from our view controller to our new Model struct.

struct Model: Equatable {

var favoriteCreature: Creature

var dreams: [Dream]

}

class DreamListViewController: UITableViewController {

var model: Model

// ...

}

Implementing undo the wrong way

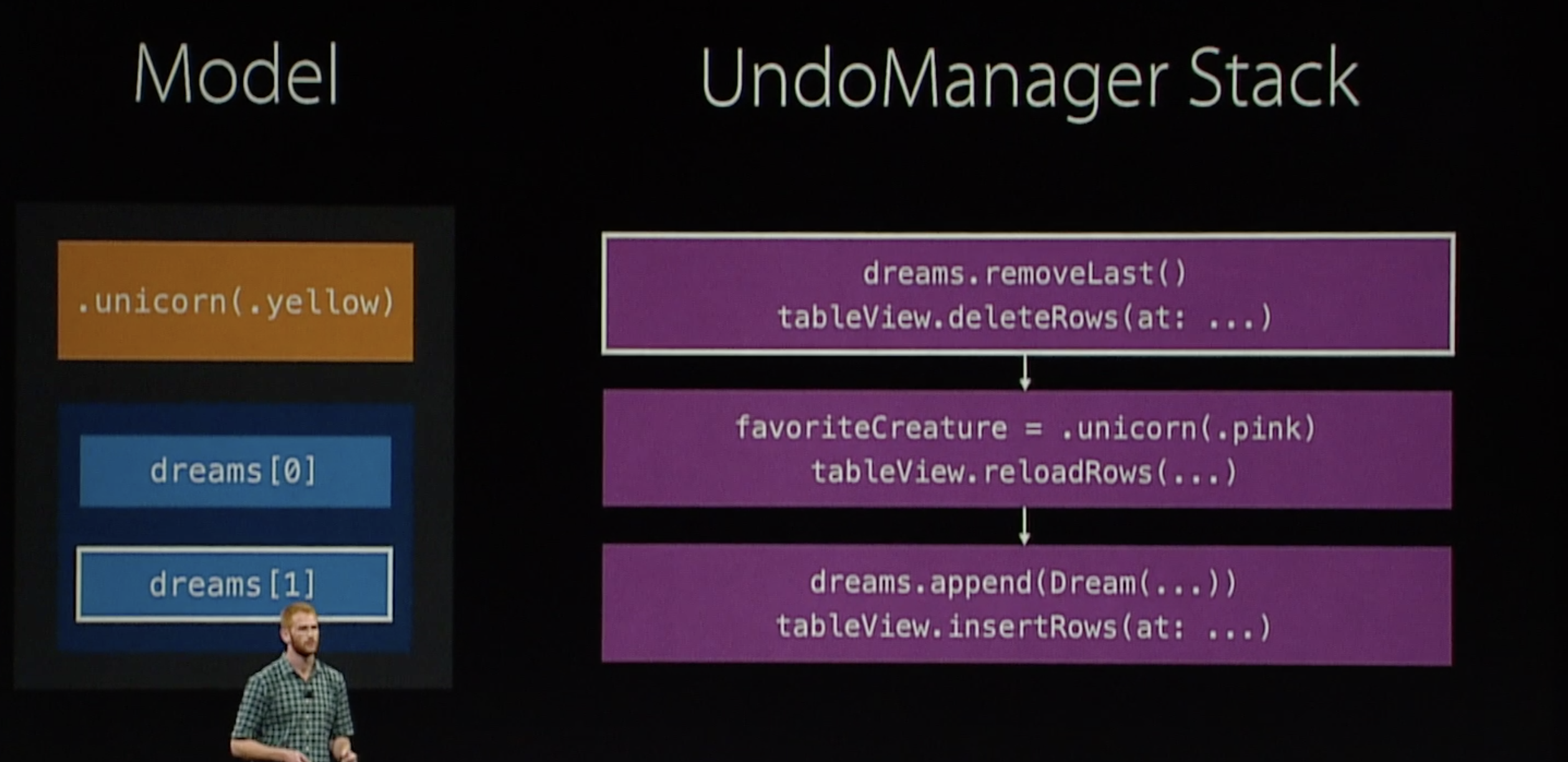

First, let's see the way undo is normally implemented. This way is a little buggy.

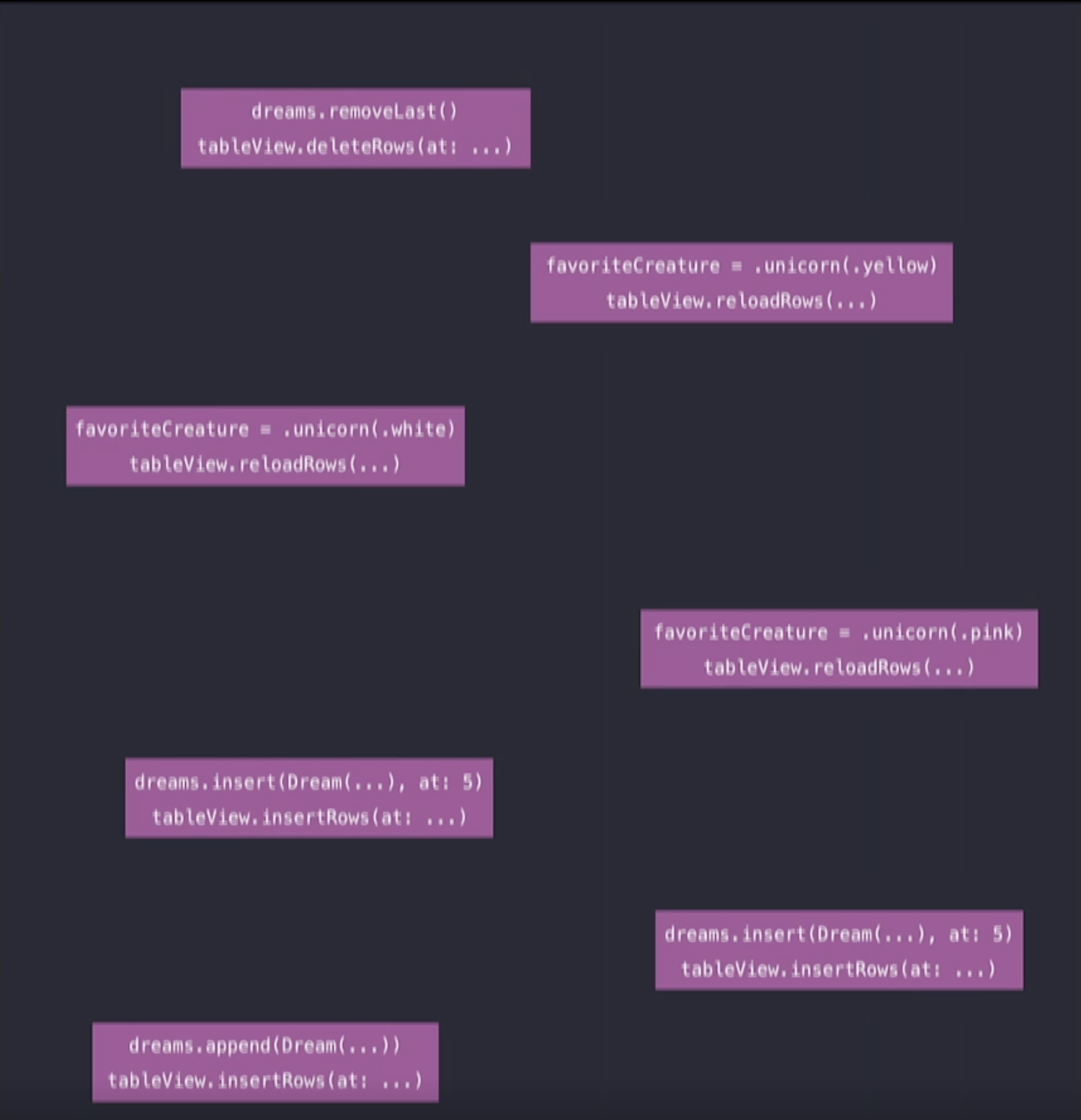

In the original version of the app, undo was represented as a series of small steps. Each step was responsible for modifying the Model and then updating the view to match.

For example, in the first undo step, we remove the dream that the user just added and then delete that row from the table view.

Subsequent undo steps would mutate the Model object even further.

What's wrong?

Mutating individual model properties and then precisely updating the view is difficult. We need to remember all parts of a view that depend on a model property, and we might forget one.

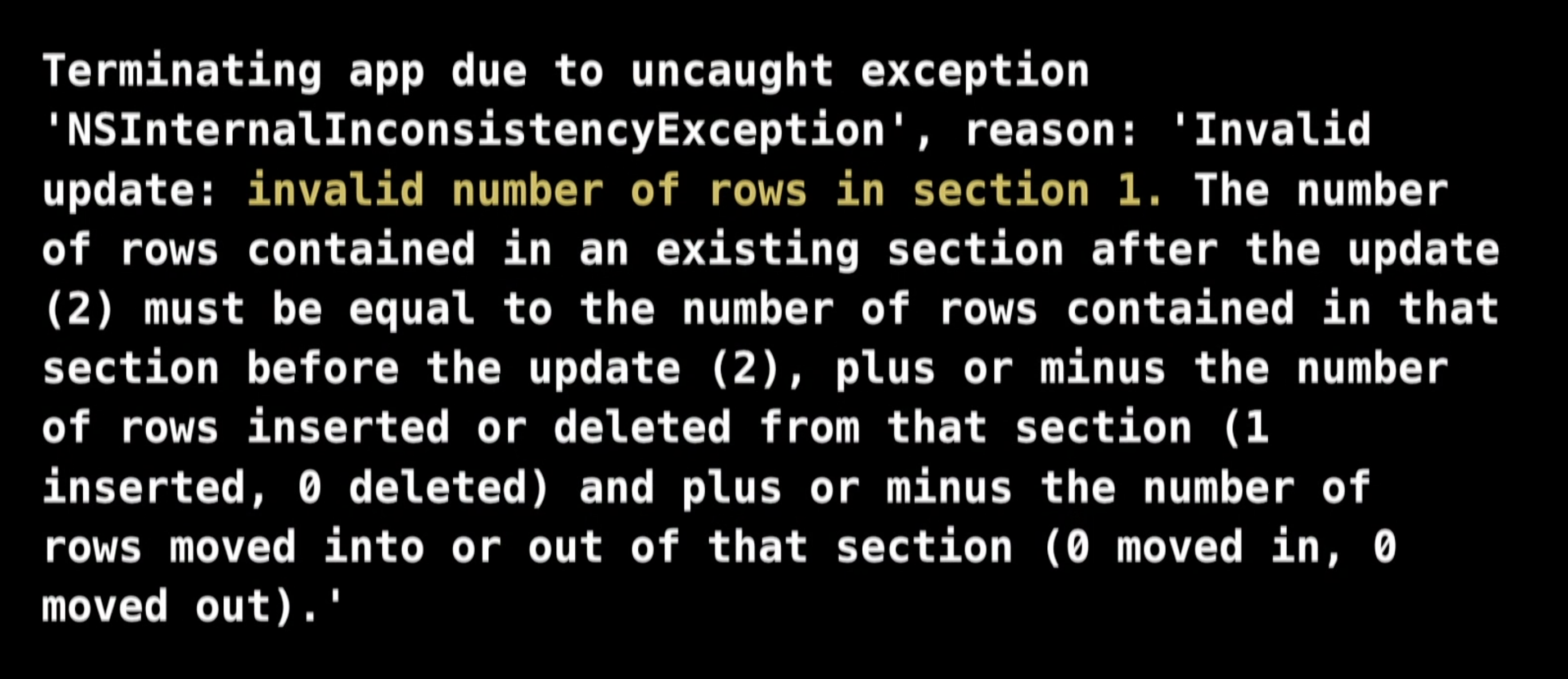

In our app, we might run into an exception like this:

Debugging these issues is also hard. Each "undo" change comes from the controller in a specific order, and each new feature in our app adds opportunities for mistakes.

There isn't one place in our code that is responsible for coordinating model and view updates.

A simpler undo implementation

Instead of recording small changes and having a stack of "diffs", each entry in our undo stack can just be a whole new Model. Performing an undo becomes as simple as:

model = undoManager.stack.removeLast()

Now that we can easily update our model, we need to figure out how to update our UI. In our view controller, whenever a model changes, we can call this modelDidChange function. Now, we only have to update UI affected by changes.

class DreamListViewController: UITableViewController {

var model: Model

// ...

func modelDidChange(old: Model, new: Model) {

if old.favoriteCreature != new.favoriteCreature {

// Reload table view section for favorite creature.

tableView.reloadSections(...)

}

// More "diff" handling for UI. See full project code.

// If user shakes device, we will reset our model to the old value.

undoManager?.registerUndo(withTarget: self) { $0.model = old }

}

}

Benefits

- Single code path for updating UI. Operations don't depend on order.

- Better local reasoning

- Values compose well with other values

Value types in controller UI state

Sharing dreams

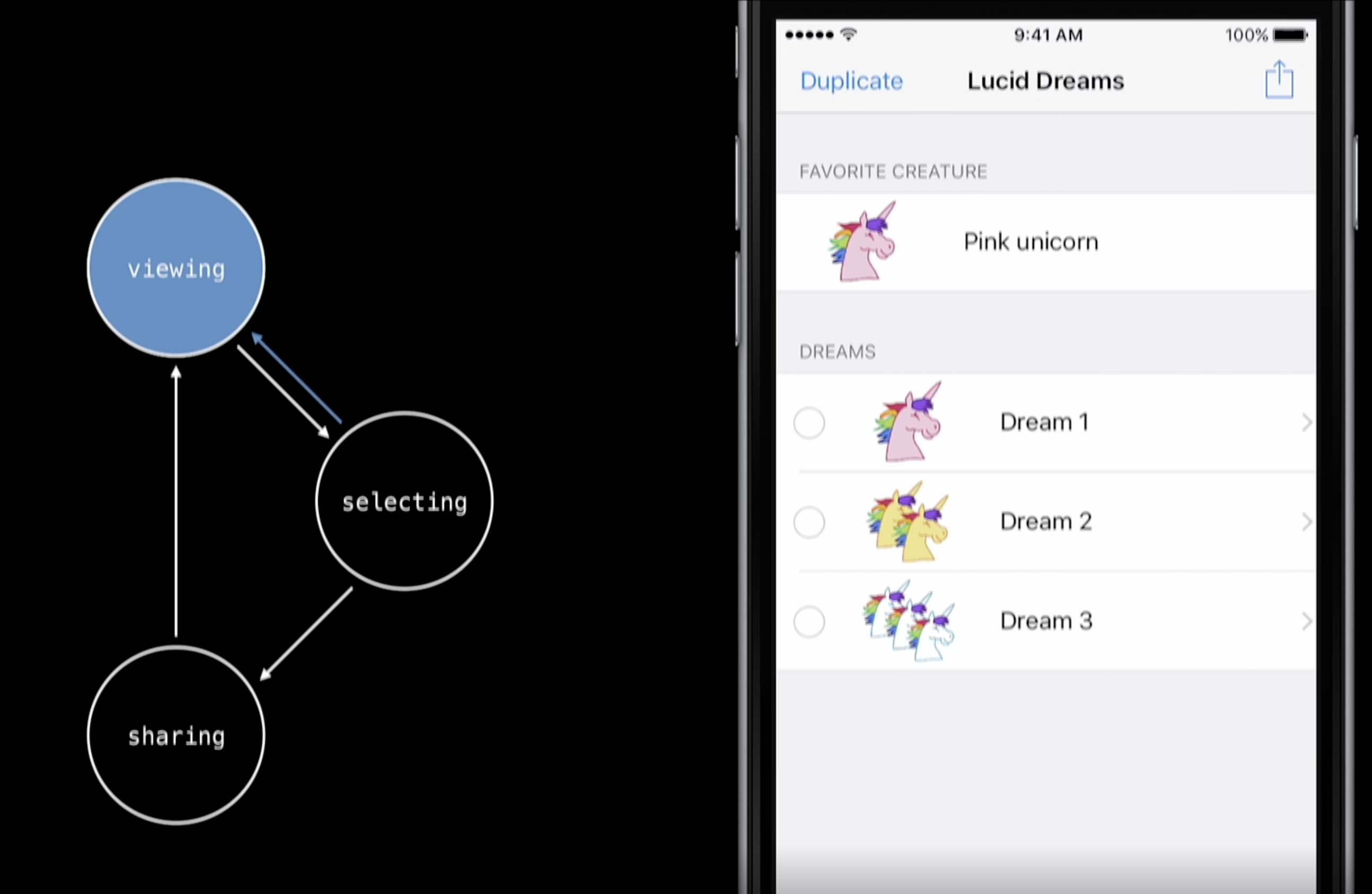

To see the home screen and the discussion of the state diagram, watch 32:10 - 32:35.

At the selecting stage, we can also tap "cancel" to go back to the viewing stage. Unfortunately, our table view doesn't exit "edit mode":

This bug exists because some state properties weren't fully cleared out when performing a state change. Each state has a corresponding property in our view controller.

class DreamListViewController: UITableViewController {

// UI state properties.

var isInViewingMode: Bool

var selectedRows: IndexSet?

var sharingDreams: [Dream]?

}

The number of UI properties in our view controller can easily explode as our feature set grows. Therefore, it's important that our properties are mutually exclusive: we don't want selectedRows to have a value at the same time as sharingDreams. Unfortunately, the way this is written, when we set one property, we have to remember to clear out every other property.

A better way to represent mutually exclusive values is to use enums. We can turn all of our UI state properties into cases on an enum value.

enum State {

case viewing

case sharing(dreams: [Dream])

case selecting(selectedRows: IndexSet)

}

class DreamListViewController: UITableViewController {

var state: State

}

Now, the invalid state bug we had before is not possible. We have the type system enforcing compile-time checks!

As a bonus, having our state all in one place makes it easier to launch our app in exactly the same state that the user left it--all we have to do is save State somewhere. See the sample project for an implementation.

Recap

Our goal is to improve local reasoning in our app across the MVC architecture. We can do this with value types and protocols.

- We started off by making our Model have value semantics.

- We made our

Dreama struct, which eliminated any implicit sharing of ourdreamvariables.

- We made our

- In the View, we built small components like

DecoratingLayoutandCascadingLayout.- These small components took advantage of protocols and generics to make themselves as reusable as possible.

- All the layout code was in one place, which improved local reasoning.

- Each type was small, isolated, and easily testable.

- In the Controller, we composed Model properties into a single type.

- We implemented undo with a single code path for all our model types and UI updates.

- We used enums for mutually exclusive state properties, reducing the potential for our UI to be in an inconsistent state.

There are many more value types in the sample project. With the exception of UIViewController or UIView subclasses, the entire app is built with value types.

Techniques and tools

- Try composition instead of inheritance to take advantage of value types

- Use protocols for generic, reusable, and testable code

- Local reasoning is really important for any programming task

- This is more general than

UIKit, mobile programming, or Swift - "How well does my code support local reasoning?"

- Value types help!

- This is more general than

Twitter

Twitter

GitHub

GitHub

www.linkedin.com

www.linkedin.com