Building Better Apps with Value Types in Swift

Description: Swift supports rich first-class value types in the form of powerful structs, which provide new ways to architect your apps. Learn about the differences between reference and value types, how value types help you elegantly solve common problems around mutability and thread safety, and discover how Swift's unique capabilities might change the way you think about abstraction.

Roadmap

- Reference semantics

- Immutability

- Value semantics

- Value types in practice

- Mixing value types and reference types

1. Reference semantics

In Swift, we get reference semantics with classes.

A Temperature Class

class Temperature {

var celsius: Double = 0

var fahrenheit: Double {

get { return celsius * 9 / 5 + 32 }

set { celsius = (newValue - 32) * 5 / 9 }

}

}

Let's set the thermostat of our home:

let home = House()

let temp = Temperature()

temp.fahrenheit = 75

home.thermostat.temperature = temp

Now let's bake something for dinner. We need to heat up the oven:

temp.fahrenheit = 425

home.oven.temperature = temp

home.oven.bake()

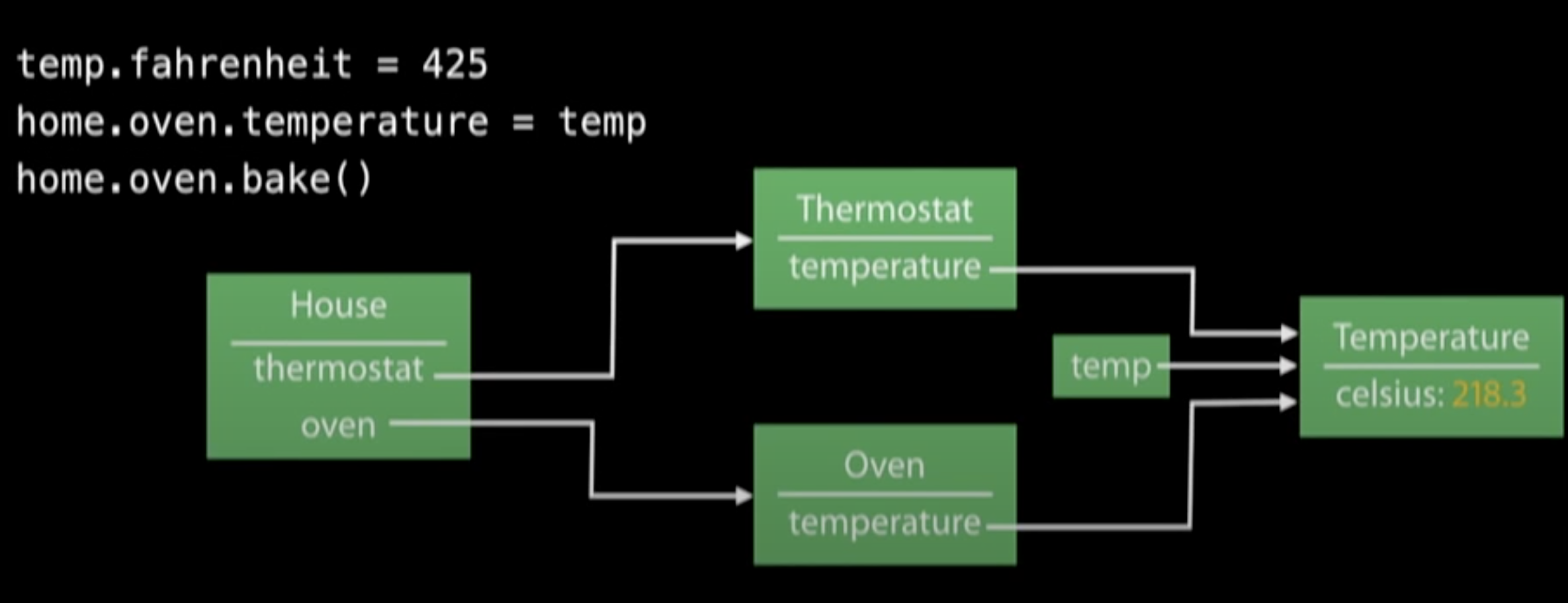

Why is it so hot in the house? Because we unintentionally shared the same temperature object, and now both the thermostat and oven are set to 425 degrees. Here's the object graph:

To prevent sharing, we need copies:

// ...

temp.fahrenheit = 75

home.thermostat.temperature = temp.copy()

temp.fahrenheit = 425

home.oven.temperature = temp.copy()

Technically, we don't need this last copy, but we might still do it so we don't run into the same issue next time. This is called defensive copying, and we end up having to do this for our Oven, Thermostat, and any other object that might require a new temperature.

class Oven {

private var _temperature: Temperature = Temperature(celsius: 0)

var temperature: Temperature {

get { return _temperature }

set { _temperature = newValue.copy() }

}

}

Copying in Cocoa[Touch] and Objective-C

Cocoa[Touch] requires copying throughout.

NSCopyingcodifies copying an objectNSString,NSArray,NSDictionary,NSURLRequest, etc. all require copying

Defensive copying pervades Cocoa[Touch] and Objective-C

NSDictionarycalls-copyon its keys so that any future changes don't affect the hash- The

copyattribute provides defensive copying on assignment

All of this results in a performance loss, and bugs can still show up any time there's missed copies.

2. Immutability

Eliminating Mutation

Functional programming languages have reference semantics with immutability. This eliminates many problems caused by reference semantics with mutation, such as unintended side effects.

However, there are several problems with immutable reference semantics:

- They can lead to awkward interfaces because we live and think in a mutable world

- They don't map efficiently to the machine model

- Eventually, we have to map to machine code which has stateful CPU, stateful caches, stateful memory and storage, etc.

An immutable Temperature class

class Temperature {

// Celsius is now always the point of reference, and it's immutable.

let celsius: Double = 0

var fahrenheit: Double {

return celsius * 9 / 5 + 32

}

// Convenience initializers.

init(celsius: Double) { self.celsius = celsius }

init(fahrenheit: Double) { self.celsius = (fahrenheit - 32) * 5 / 9 }

}

This leads to awkward interfaces. Before, if we wanted to increase our temperature by 10 degrees Fahrenheit, it was simple:

// With mutability

home.oven.temperature.fahrenheit += 10.0

Without mutability, we have to get the temperature and then create a new temperature object:

// Without mutability

let temp = home.oven.temperature

home.oven.temperature = Temperature(fahrenheit: temp.fahrenheit + 10.0)

This is more awkward and less performant because we need to allocate another object on the heap.

Most importantly, this solution is still not truly immutable. We're still mutating the Oven when we set a new temperature. A truly immutable system would create a new temperature, a new oven, and a new home...which is still awkward.

Sieve of Eratosthenes

Getting a little more mathematical--the Sieve of Eratosthenes is an ancient algorithm for computing prime numbers. This algorithm lends itself very well to mutation.

This is the mutable implementation of the algorithm in Swift:

func primes(n: Int) -> [Int] {

var numbers = [Int](2..<n)

for i in 0..<n - 2 {

guard let prime = numbers[i] where prime > 0 else { continue }

for multiple in stride(from: 2 * prime - 2, to: n - 2, by: prime) {

numbers[multiple] = 0

}

}

return numbers.filter { $0 > 0 }

}

The algorithm basically creates an array of numbers from 2 to n. The outer loop walks through the array. The inner loop, going right, sets all multiples of that number to 0. The algorithm then returns only non-zero values from the array, which is all the prime numbers.

Functional Sieve of Eratosthenes

We can also express this algorithm in a world without mutation. Here is the implementation in Haskell, a purely functional language:

primes = sieve [2..]

sieve [] = []

sieve (p : xs) = p : sieve [x | x <- xs, x 'mod' p > 0]

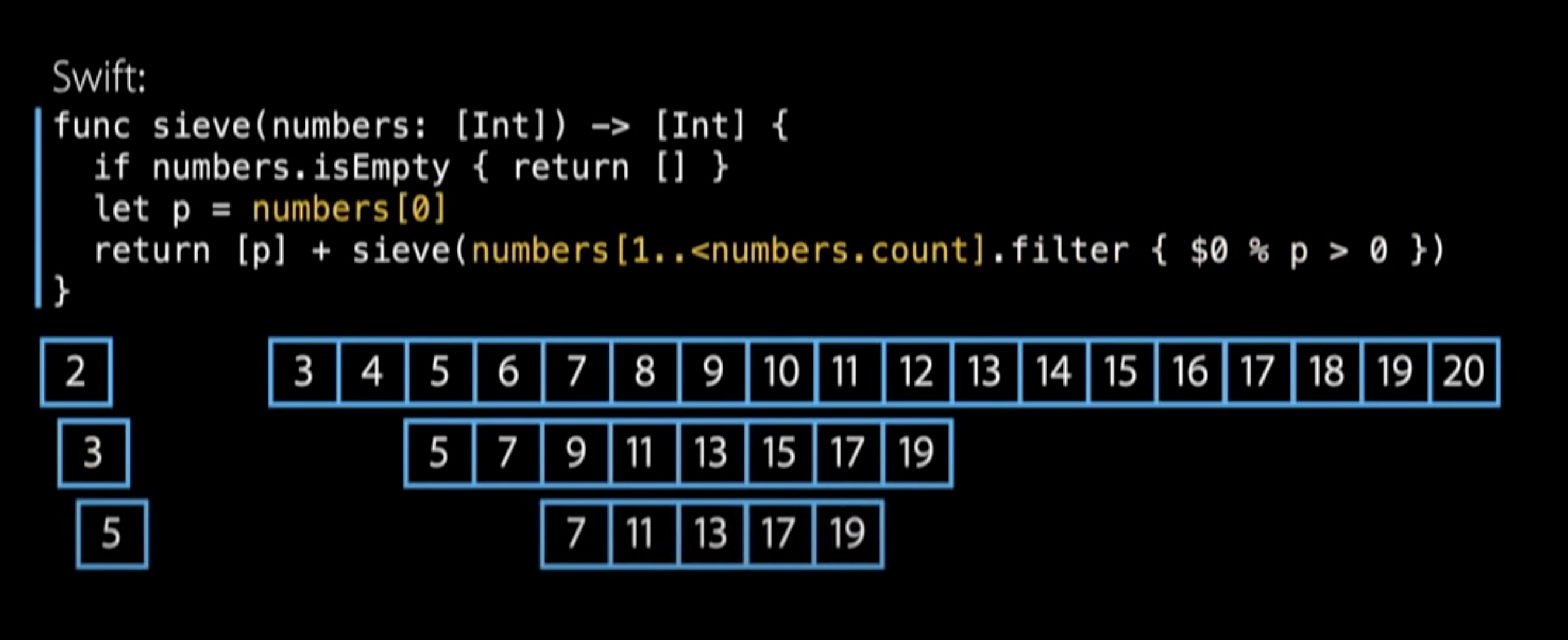

We can do exactly the same thing in Swift:

func sieve(numbers: [Int]) -> [Int] {

guard !numbers.isEmpty else { return [] }

let p = numbers[0]

return [p] + sieve(numbers[1..<numbers.count]).filter { $0 % p > 0 }

}

This immutable algorithm is very similar to the mutable one. Assuming the array isn't empty, we take out the first number (2), which is always prime. We then perform a filter operation and copy over all array elements that are not divisible by that number. Then we recurse, and we build up the prime numbers on the left-hand diagonal. These are concatenated together to get the result.

Unfortunately, this algorithm is not similar in performance. The problem is the filter operation. In the original mutating algorithm, we only walked over multiples of the prime number, which get more and more sparse as the multiple increases. Moreover, we only have to do addition to get to the next element. Overall, the mutating version does less work per element.

Immutability in Cocoa[Touch]

Cocoa[Touch] has a number of immutable classes:

NSDate,NSURL,UIImage,NSNumber, etc.- Improved safety (no need to use copy)

There are also downsides to immutability. In Objective-C, if we wanted to start at our home directory and successively add path components, we would have to create a new NSURL object on each loop iteration:

NSURL *url = [[NSURL alloc] initWithString: NSHomeDirectory()];

NSString *component;

while ((component = getNextSubdir())) {

// Create new object on heap, copy over all string data, discard old object...

url = [url URLByAppendingPathComponent: component];

}

There's a better way to do this--we could just add the components to an array and create a single new NSURL instance at the end. However, if we want to be truly immutable, we have to create a new array on each iteration of the loop...which is still O(n^2):

NSArray<NSString *> *array = [NSArray arrayWithObject: NSHomeDirectory()];

NSString *component;

while ((component = getNextSubdir())) {

// Create new array, copy over elements, discard old array...

array = [array arrayByAddingObject: component];

}

url = [NSURL fileURLWithPathComponents: array];

The correct way to do this in Cocoa is to use mutation--we need to store all our components into an NSMutableArray and then create the NSURL at the end, which is O(n):

NSMutableArray<NSString *> *array = [NSMutableArray array];

[array addObject: NSHomeDirectory()];

NSString *component;

while ((component = getNextSubdir())) {

[array addObject: component]; // Mutate array object.

}

url = [NSURL fileURLWithPathComponents: array];

Immutability is a good thing: it makes the reference semantics world easier to reason about, but we still can't go entirely immutable.

3. Value Semantics

Let's take a different approach. We like mutation because it's easy to use when done correctly, but the problem is data sharing.

Value types solve this problem. Mutating one variable of some value type will never affect a different variable:

var a: Int = 17

var b = a

assert(a == b)

b += 25

print("a = \(a), b = \(b)") // Prints "a = 17, b = 42"

We're used to this with fundamental types like numbers and perhaps CGPoint--we would never expect that a change to b would affect a.

We can take this same principle and extend it to more complex types.

Value types compose

- All of Swift's "fundamental" types are value types

Int,Double,String, ...

- All of Swift's collections are value types

Array,Set,Dictionary, ...

In Swift, any tuple, struct, or enum that contains only value types is also a value type. It's very easy to build rich abstractions entirely in the world of value types.

Value types are distinguished by value

Equality is established by the value of a variable, not its identity or how we arrived at the value.

This makes perfect sense for fundamental types like Integers...

var a: Int = 5

var b: Int = 2 + 3

assert(a == b) // True

...so we can extend it to less fundamental types like collections:

var a: [Int] = [1, 2, 3]

var b: [Int] = [3, 2, 1].sort(<)

assert(a == b) // True

Value types should implement Equatable

We can't understand our code unless we have reflexive, symmetric, and transitive notions of equality.

protocol Equatable {

/// Reflexive: `x == x` is `true`

/// Symmetric: If `x == y` then `y == x`

/// Transitive: If `x == y` and `y == z`, then `x == z`

func ==(lhs: Self, rhs: Self) -> Bool

}

Fortunately, it's very easy to conform to Equatable. After declaring conformance, we just have to implement the equality operator for our properties. Generally speaking, when we compose value types out of other value types, we can rely on the underlying == operators defined for each property.

In this example, we define equality for CGPoint by using equality for Int, another value type:

extension CGPoint: Equatable {}

func ==(lhs: CGPoint, rhs: CGPoint) -> Bool {

return lhs.x == rhs.x && lhs.y == rhs.y

}

Value semantics version of Temperature

Let's make Temperature a struct now.

struct Temperature: Equatable {

var celsius: Double = 0

var fahrenheit: Double {

get { return celsius * 9 / 5 + 32 }

set { celsius = (newValue - 32) * 5 / 9 }

}

}

func ==(lhs: Temperature, rhs: Temperature) -> Bool {

return lhs.celsius == rhs.celsius

}

Unfortunately, we run into an error when using this new struct:

let temp = Temperature()

temp.fahrenheit = 75 // ERROR: cannot assign to property: 'temp' is a 'let' constant

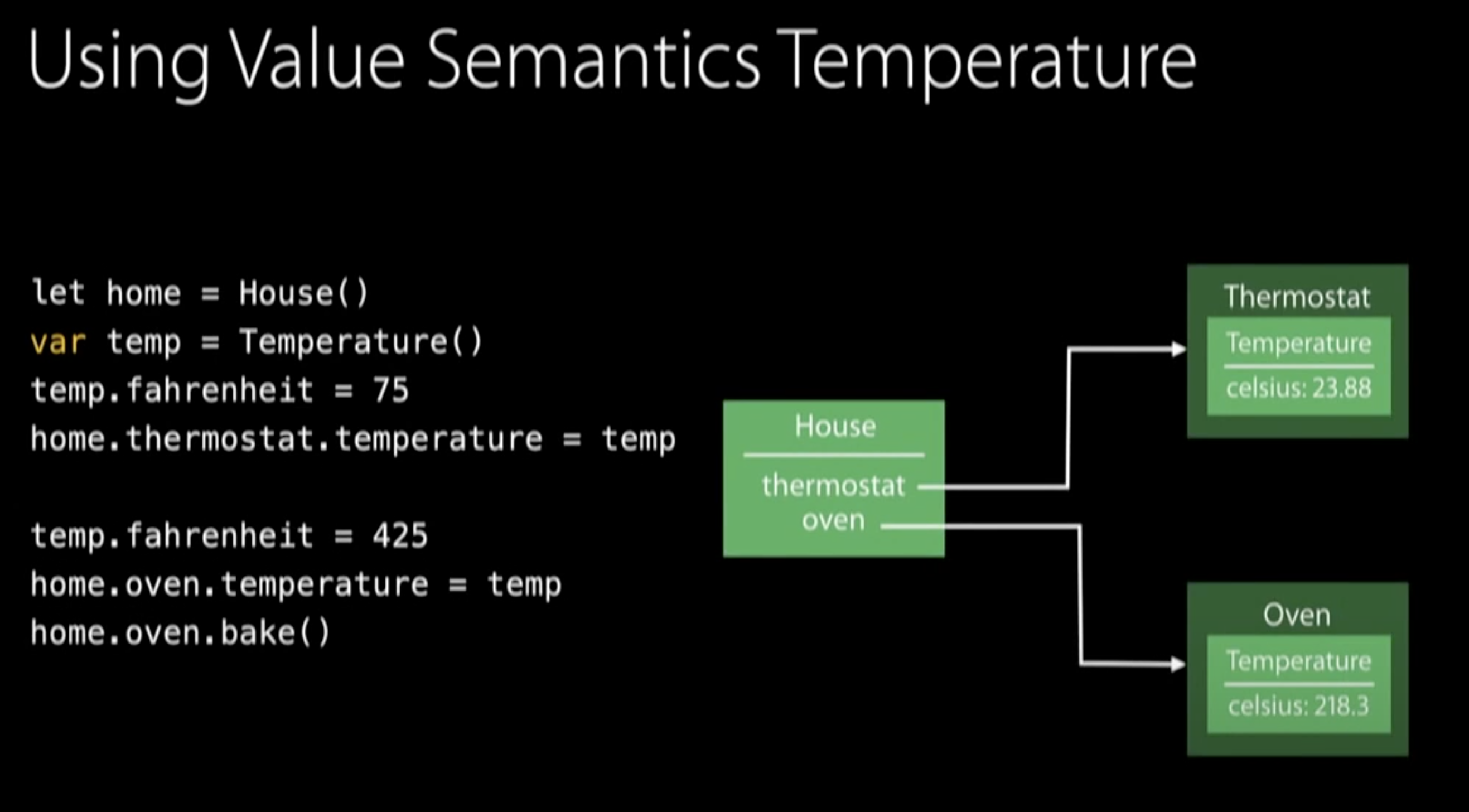

All we have to do is change let to var, and our code works perfectly fine because both thermostat and oven have their own instances of Temperature values. There is no more sharing, and the values are also inlined into the struct so we get better memory usage and performance:

Mutation when we want it, but not when we don't

Value semantics work well in Swift because we already have keywords to indicate mutability.

let means the value will never change, which is a very strong statement!

let numbers = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

var means we can update the value without affecting any other values in our code (no data sharing).

var strings = [String]()

for x in numbers {

strings.append(String(x))

}

This gives us controlled mutability with strong guarantees throughout our code.

Freedom from race conditions

Passing value types across thread boundaries means we don't have to worry about race conditions on those types.

In an array with reference semantics, the code below would cause a race condition because the same array would be shared by both threads. In an array with value semantics, we get logical copies each time, so each thread gets its own array.

var numbers = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

scheduler.processNumbersAsynchronously(numbers)

for i in 0..<numbers.count {

numbers[i] = numbers[i] * 1

}

scheduler.processNumbersAsynchronously(numbers)

What about all those copies?

Copies are cheap (O(1)) with value semantics. Let's build this from the ground-up:

- Copying a low-level, fundamental type is constant time (

Int,Double, ...)- Just requires copying a few bytes, which happens inside the processor.

- Copying a struct, enum, or tuple of value types is also constant time (

CGPoint, ...)- Fixed number of fields, so it's not

O(n). - Copying each "building block" is constant time, so copying the whole object is also constant time.

- Fixed number of fields, so it's not

- Extensible data structures use copy-on-write

- Copying involves a fixed number of reference counting operations.

- Copying only happens at the point of mutation. This is "sharing behind the scenes", but not logical sharing. These are treated as distinct values when they need to be.

String,Array,Set,Dictionary, etc.

Recap: Value semantics are simple and efficient

- Different variables are logically distinct

- Mutability when we want it

- Copies are cheap

4. Value types in practice

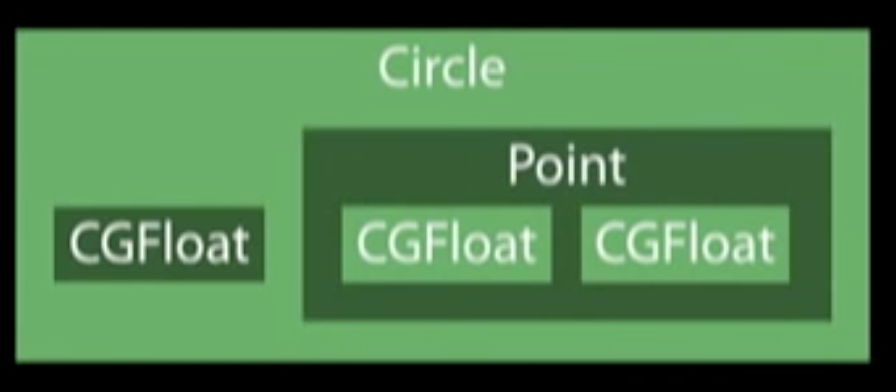

We're going to build a diagram made out of some simple value types like circles and polygons.

Circle

struct Circle: Equatable {

var center: CGPoint

var radius: Double

}

func ==(lhs: Circle, rhs: Circle) {

return lhs.center == rhs.center && lhs.radius == rhs.radius

}

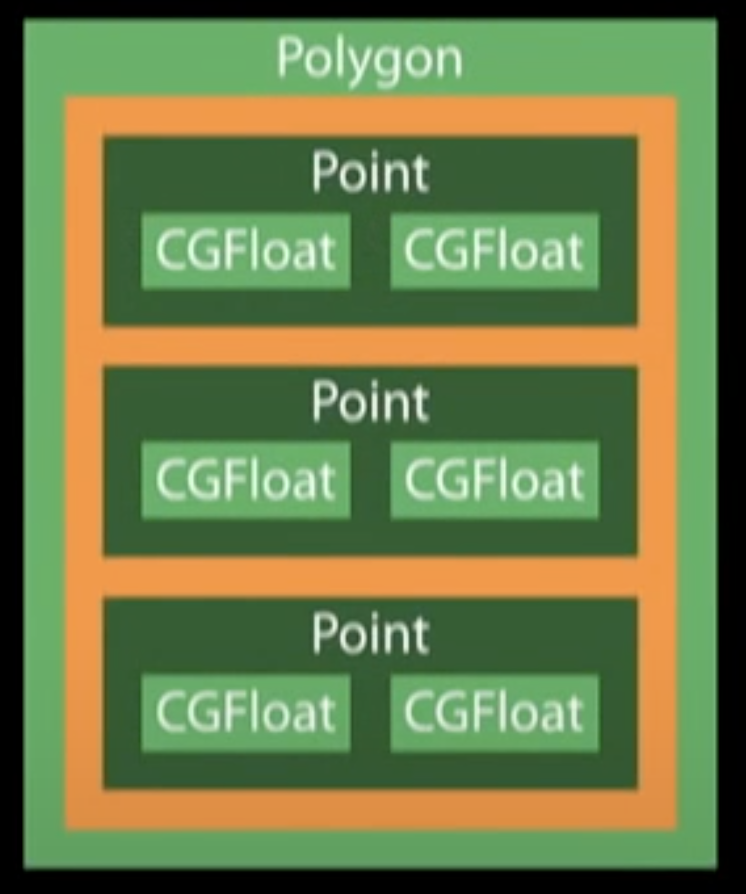

Polygon

struct Polygon: Equatable {

var corners = [CGPoint]()

}

func ==(lhs: Polygon, rhs: Polygon) {

return lhs.corners == rhs.corners

}

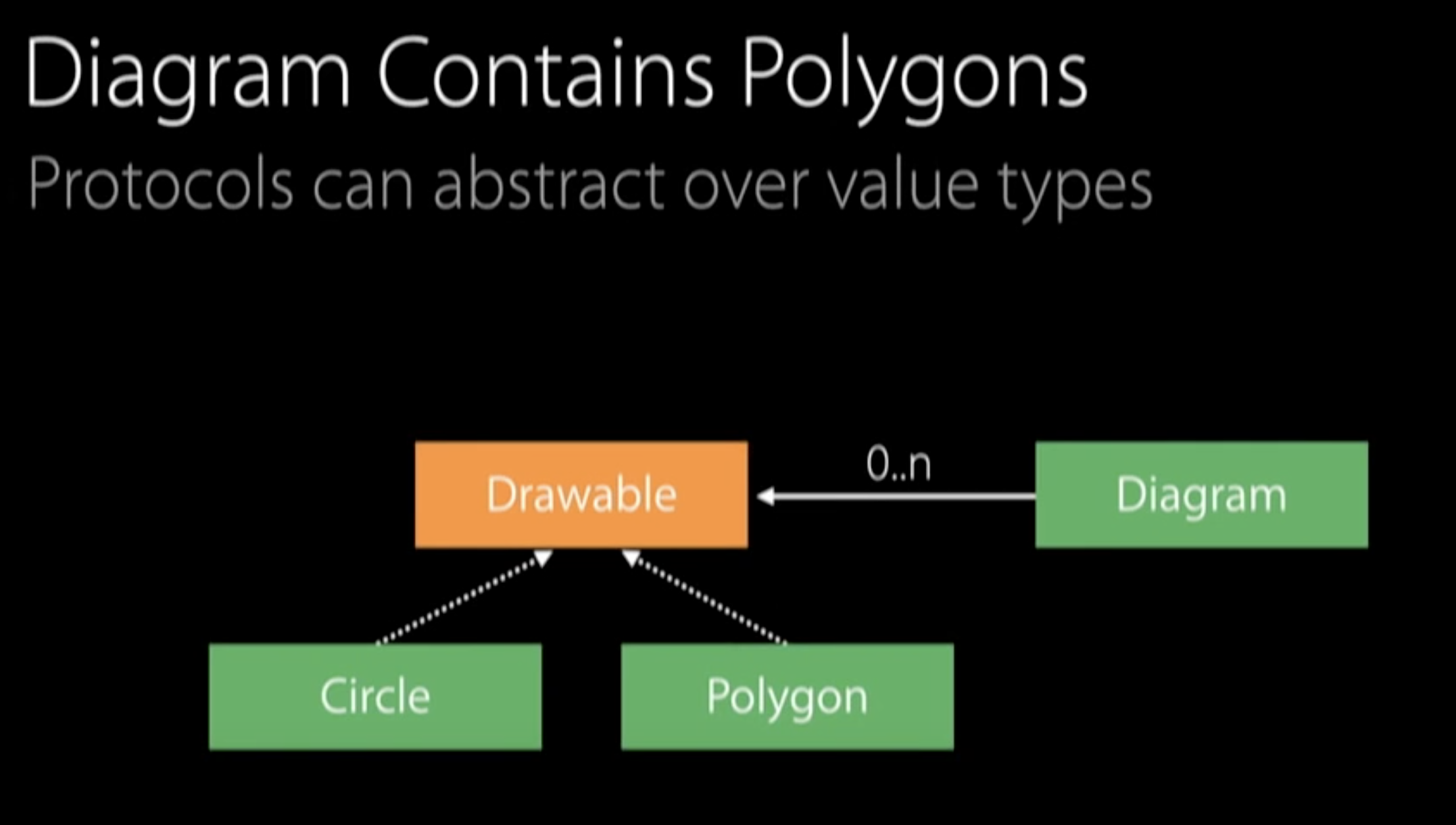

Diagrams need to contain either shape

We can just make both Circle and Polygon conform to a new protocol, Drawable. For more information, see Protocol-Oriented Programming in Swift.

Here's the protocol and conforming implementations:

protocol Drawable {

func draw()

}

extension Polygon: Drawable {

func draw() {

let ctx = UIGraphicsGetCurrentContext()

CGContextMoveToPoint(ctx, corners.last!.x, corners.last!.y)

for point in corners {

CGContextAddLineToPoint(ctx, point.x, point.y)

}

CGContextClosePath(ctx)

CGContextStrokePath(ctx)

}

}

extension Circle: Drawable {

func draw() {

let arc = CGPathCreateMutable()

CGPathAddArc(arc, nil, center.x, center.y, radius, 0, 2 * π, true)

CGContextAddPath(ctx, arc)

CGContextStrokePath(ctx)

}

}

Creating Diagram

struct Diagram {

var items = [Drawable]()

mutating func addItem(item: Drawable) {

items.append(item)

}

func draw() {

for item in items {

item.draw()

}

}

}

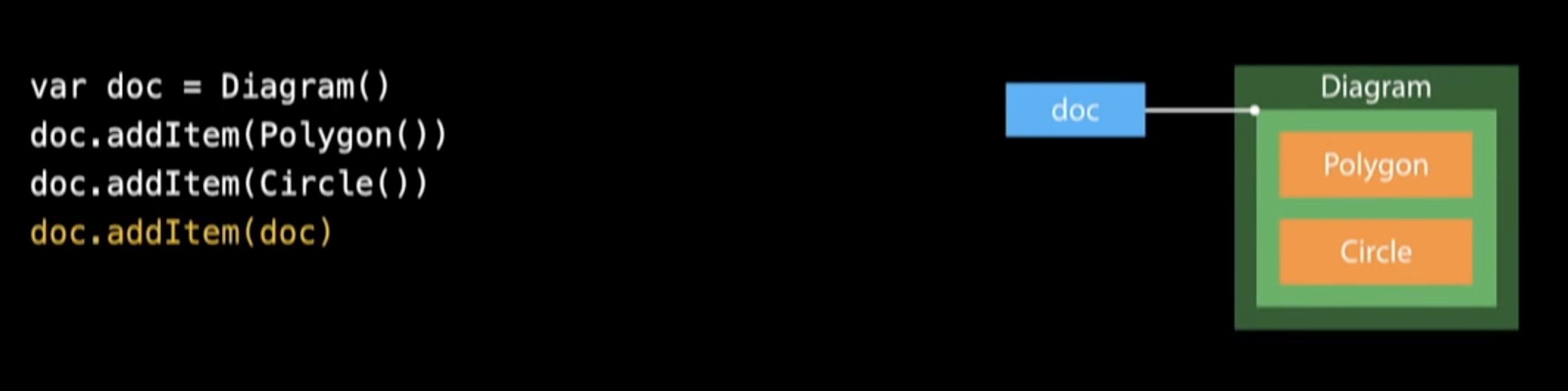

Using the diagram

Making Diagram Equatable

The straightforward implementation would be to just use equality for each item in the items array, but this causes an error:

extension Diagram: Equatable {}

func ==(lhs: Diagram, rhs: Diagram) {

// ERROR: binary operator '==' cannot be applied to two [Drawable] operands

return lhs.items == rhs.items

}

For more information, see Protocol-Oriented Programming in Swift.

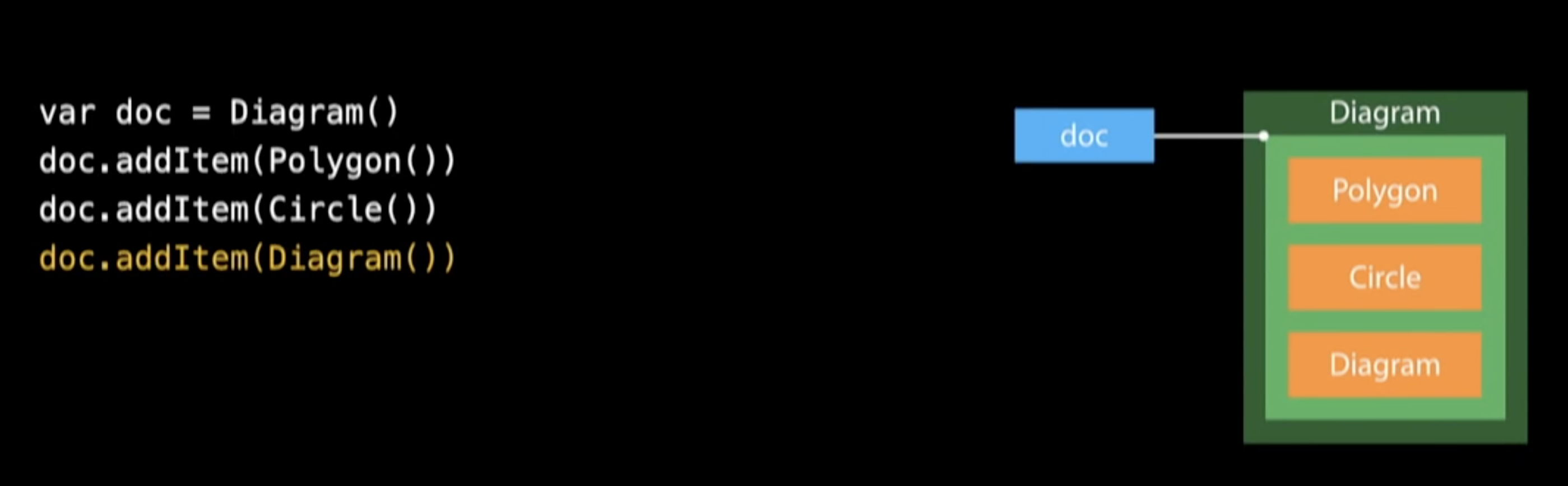

Making Diagram Drawable

Diagram already has a draw() function, so all we have to do is declare conformance:

struct Diagram: Drawable { ... }

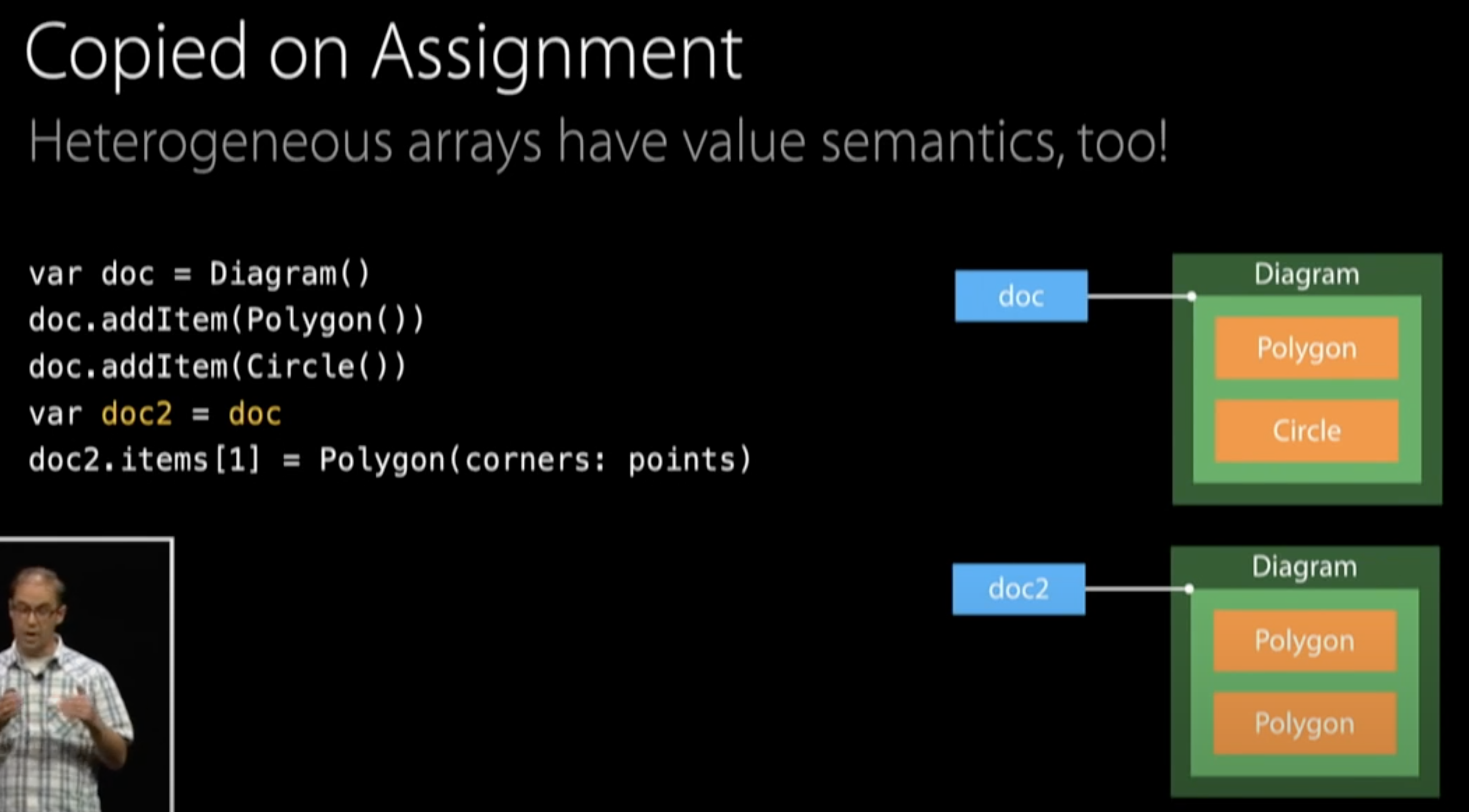

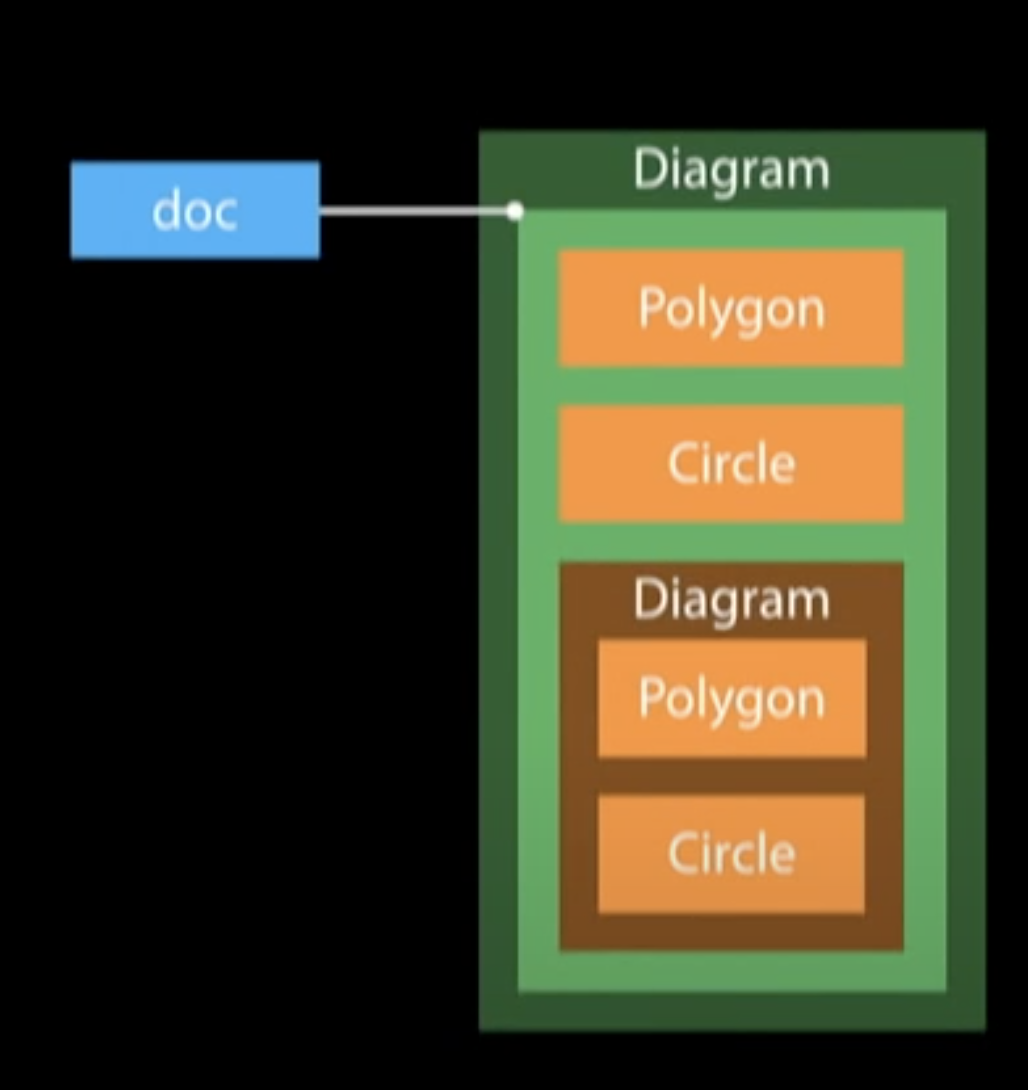

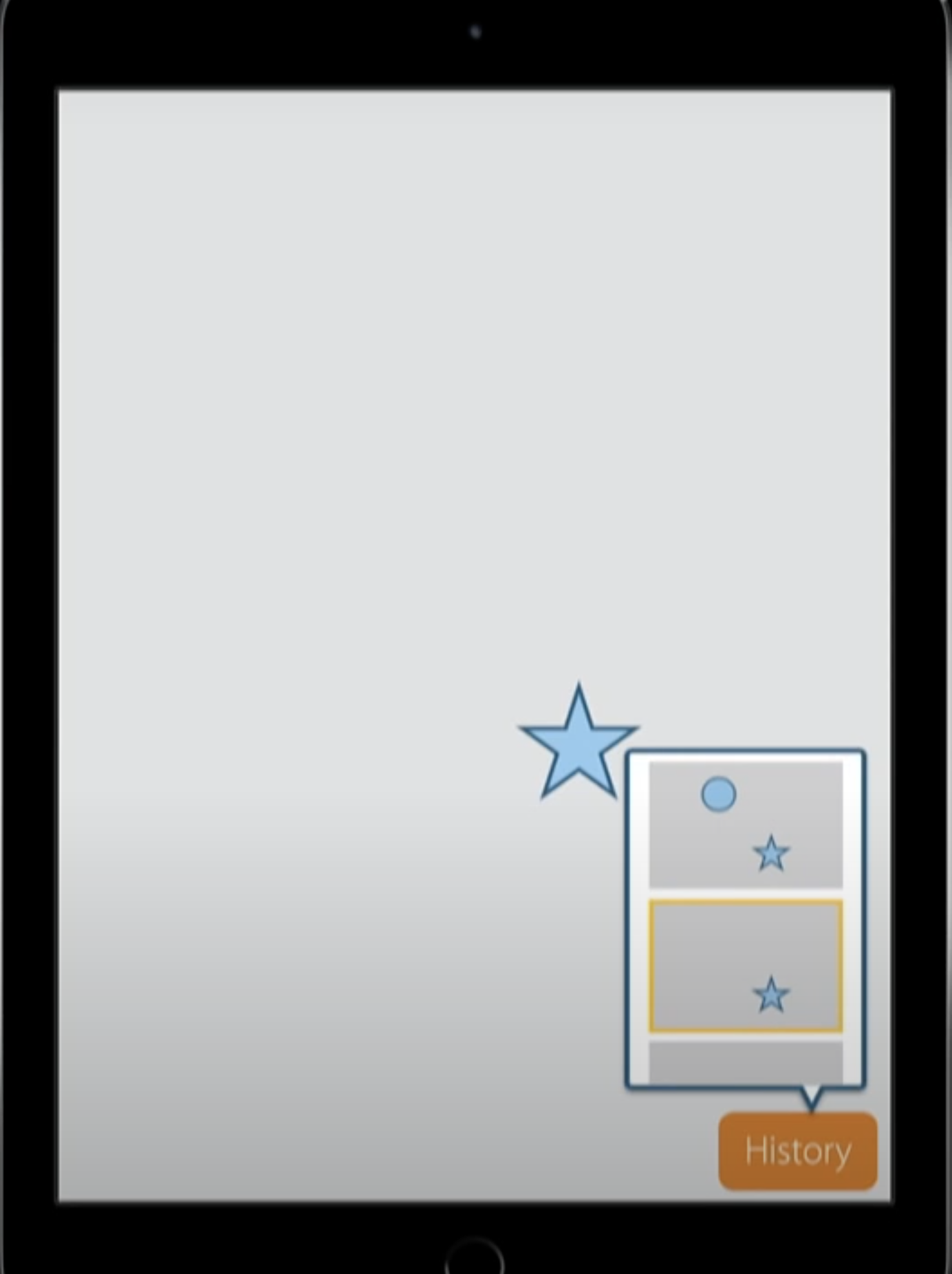

We can actually add a new instance of Diagram to the first Diagram, and it's all contained inside the items array:

We can even add the diagram to its own items array:

Why doesn't this cause infinite recursion? Let's look at the implementation of Diagram.draw:

func draw() {

for item in items {

item.draw()

}

}

If Diagram used reference semantics, we would get infinite recursion. Calling draw would iterate through items, and eventually it would call its own draw again...and again.

However, we're using value semantics. We get an entirely new copy of Diagram that is not equal to the original Diagram because it doesn't have itself in its items array:

5. Mixing value types and reference types

Reference types often contain value types

Value types are generally used for "primitive" data of objects:

class Button: Control {

var label: String

var enabled: Bool

// ...

}

A value type can contain a reference

Copies of the value type will share the reference:

struct ButtonWrapper {

var button: Button

}

Maintaining value semantics requires special considerations:

- How do we cope with mutation of the referenced object?

- How does the reference identity affect equality?

Immutable references are okay!

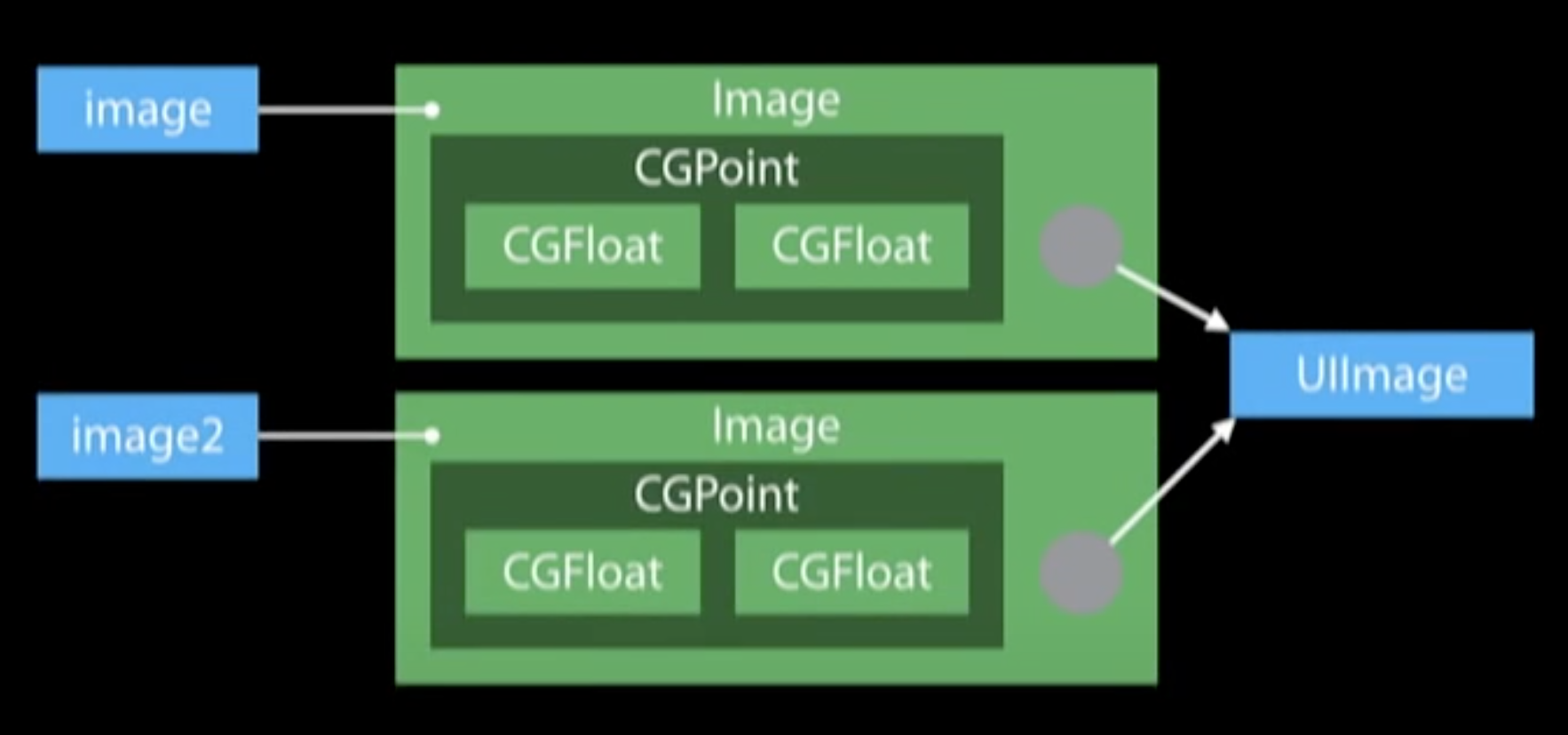

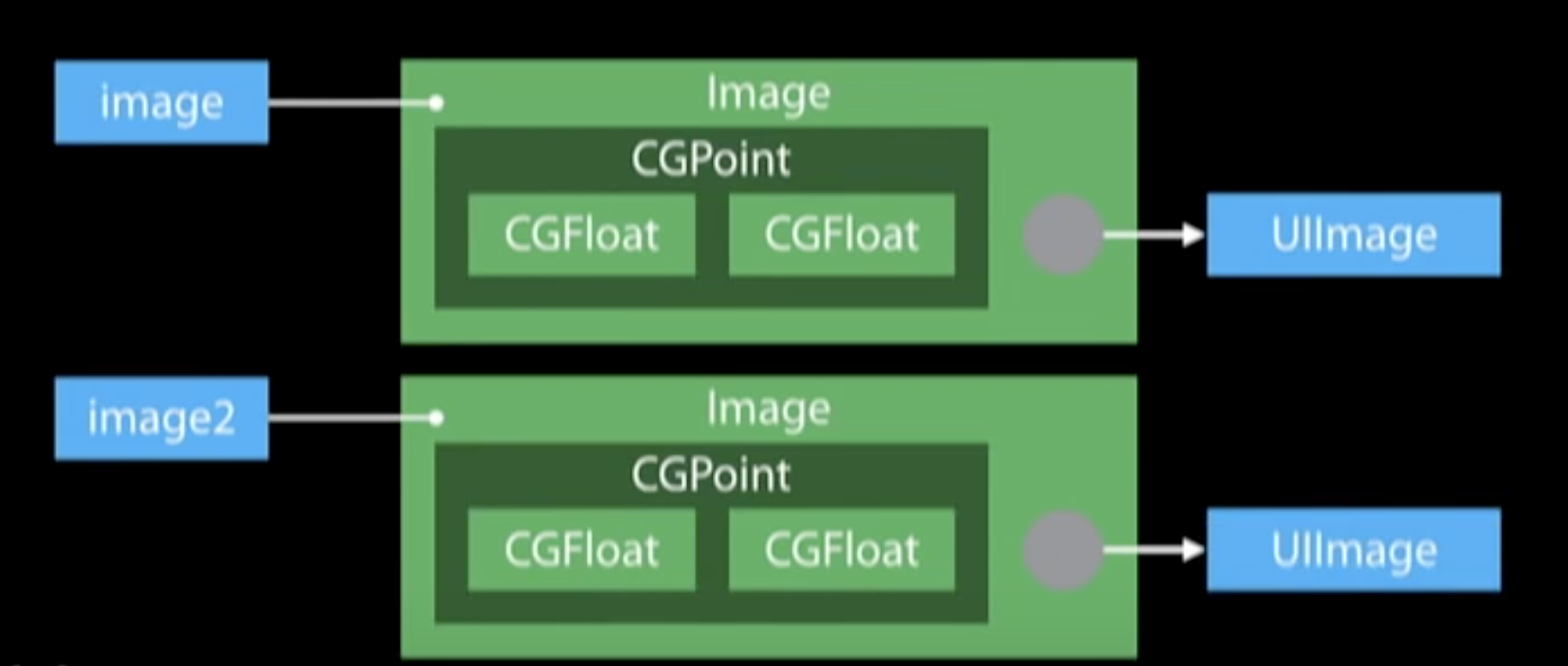

Let's create an Image struct that wraps a reference type, UIImage:

struct Image: Drawable {

var topLeft: CGPoint

var image: UIImage

}

Now, let's create 2 images which point to the same UIImage object:

var image = Image(

topLeft: CGPoint(x: 0, y: 0),

image: UIImage(imageNamed: "San Francisco")!

)

var image2 = image

This is not going to cause issues (like with Temperature) because UIImage is immutable. We don't have to worry about image2 mutating the image it shares with image.

Immutable references and Equatable

Let's implement Equatable for our struct. Notice the === operator that checks if both image properties point to the same UIImage in memory:

extension Image: Equatable {}

func ==(lhs: Image, rhs: Image) -> Bool {

return lhs.topLeft == rhs.topLeft && lhs.image === rhs.image

}

This would work in the example we have, but what if we create 2 separate UIImages using the same underlying bitmap?

These should also be considered equal. However, even though both UIImages were created with the same bitmap, they would have different references, and our === operator would consider these images unequal.

Reference identity is not enough

Instead, we should use the isEqual method that UIImage inherits from NSObject:

func ==(lhs: Image, rhs: Image) -> Bool {

return lhs.topLeft == rhs.topLeft && lhs.image.isEqual(rhs.image)

}

References to mutable objects

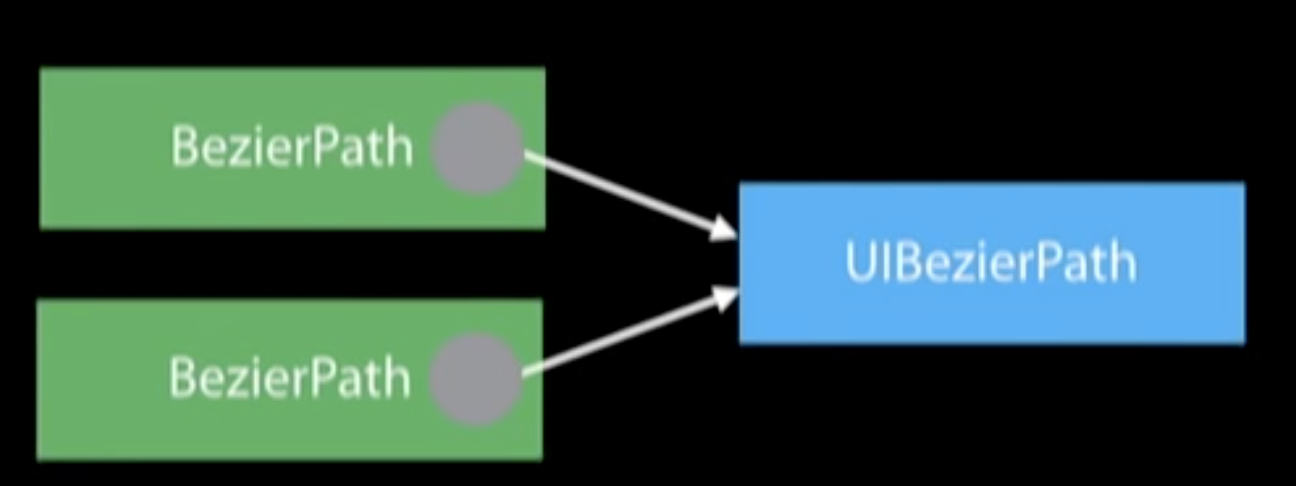

This BezierPath value type is made up entirely of a reference to a mutable type, UIBezierPath. If we have 2 BezierPaths pointing to the same reference, calling addLineToPoint is going to cause problems for both objects.

struct BezierPath: Drawable {

var path = UIBezierPath()

var isEmpty: Bool {

return path.empty

}

// Potential problems

func addLineToPoint(point: CGPoint) {

path.addLineToPoint(point)

}

}

Also notice that there is no mutating keyword because path is a reference type. This is a bad situation because we're not maintaining value semantics even though we're using value types.

Copy-on-write

- Unrestricted mutation of referenced objects breaks value semantics

- Separate non-mutating operations from mutating ones

- Non-mutating operations are always safe

- Mutating operations must first copy

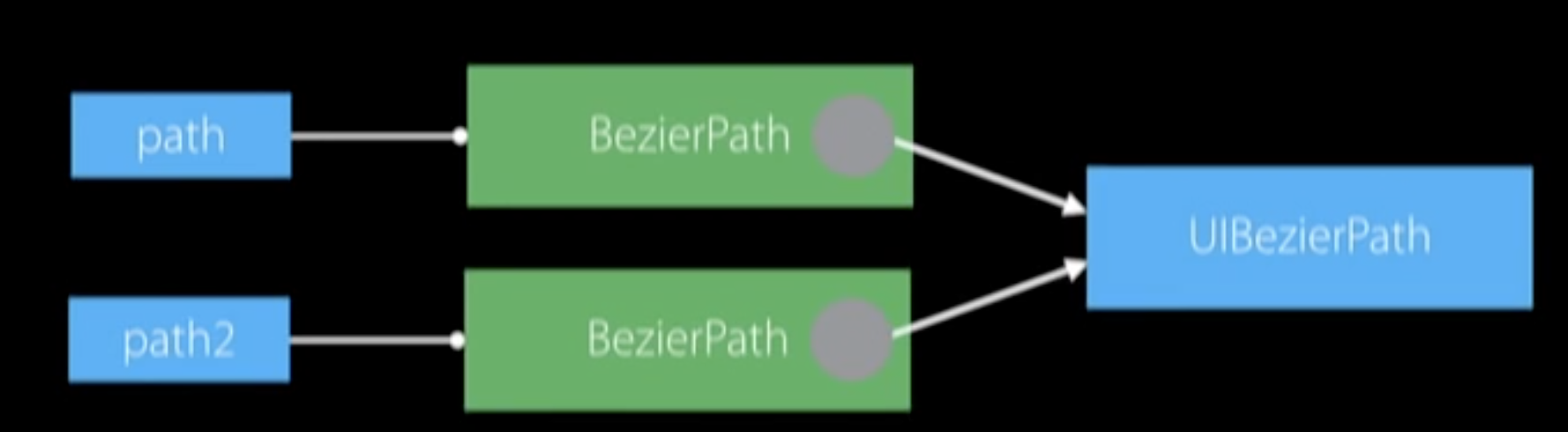

Copy-on-write in action

We need to separate accessors for reading and writing so we maintain value semantics.

struct BezierPath: Drawable {

private var _path = UIBezierPath()

var pathForReading: UIBezierPath {

return _path

}

var pathForWriting: UIBezierPath {

mutating get {

_path = _path.copy() as! UIBezierPath

return _path

}

}

var isEmpty: Bool {

return pathForReading.empty

}

mutating func addLineToPoint(point: CGPoint) {

pathForWriting.addLineToPoint(point)

}

}

Now, if we use BezierPath, we share references as long as there's no mutation...

var path = BezierPath()

var path2 = path

if path.empty { print("Path is empty") }

...and when we mutate, we first create a copy so path2 is not affected:

path.addLineToPoint(CGPoint(x: 10, y: 20))

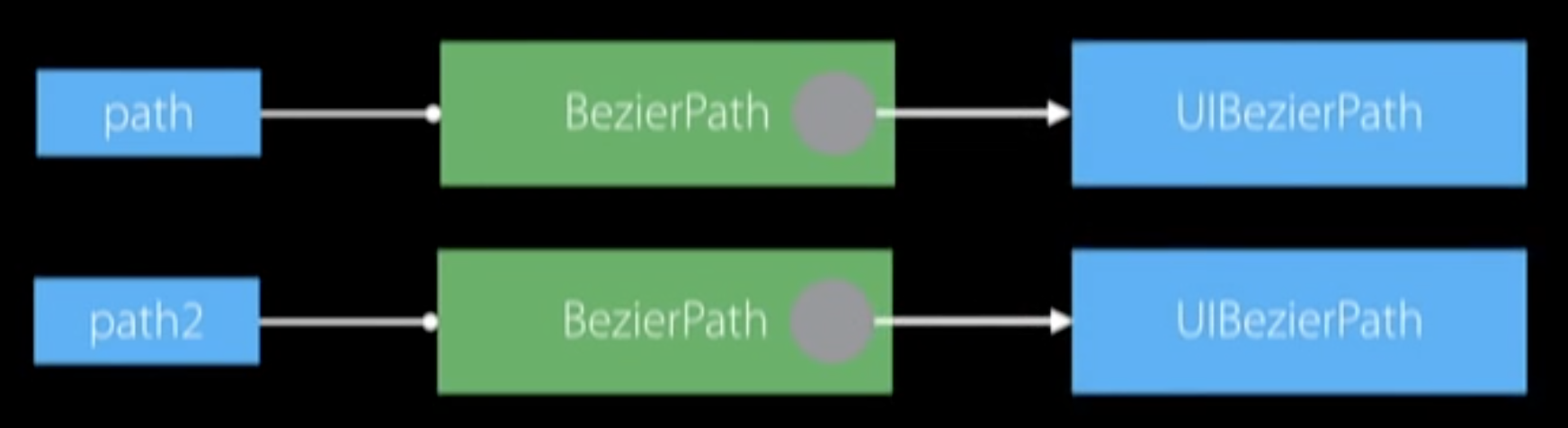

Forming a path from a Polygon

Immutable algorithm:

extension Polygon {

var path: BezierPath {

var result = BezierPath()

result.moveToPoint(corners.last!)

for point in corners {

// Copies `BezierPath` in every iteration of the loop!

result.addLineToPoint(point)

}

return result

}

}

Because of the copies, we may see a performance hit. A better implementation carefully uses mutation:

extension Polygon {

var path: BezierPath {

var result = UIBezierPath() // Reference type

result.moveToPoint(corners.last!)

for point in corners {

result.addLineToPoint(point) // Mutate in every iteration

}

return BezierPath(path: result) // Create value type at end

}

}

Uniquely referenced Swift objects

Swift can tell us if objects are uniquely referenced, so we can avoid making copies if we don't need to. The Swift Standard Library uses this feature extensively.

struct MyWrapper {

var _object: SomeSwiftObject

var objectForWriting: SomeSwiftObject {

mutating get {

if !isUniquelyReferencedNonObjc(&_object) {

_object = _object.copy()

}

return _object

}

}

}

Recap: Mixing value types and reference types

- Maintaining value semantics requires special considerations

- Copy-on-write enables efficient value semantics when wrapping Swift reference types

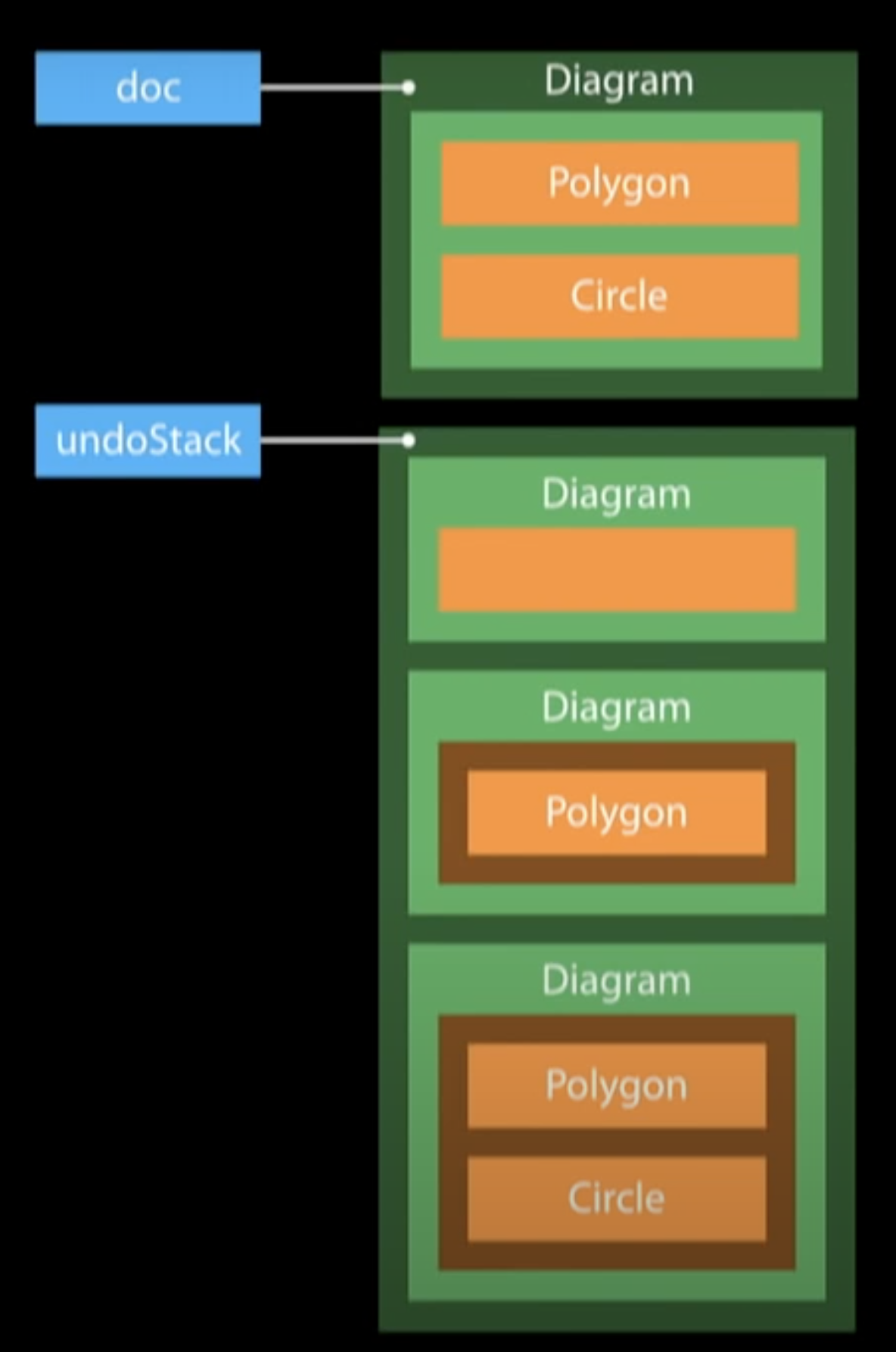

Implementing undo with value types

We're going to create a diagram and an array of diagrams. With every mutation, we add our doc to our diagram array.

var doc = Diagram()

var undoStack = [Diagram]()

undoStack.append(doc)

doc.addItem(Polygon())

undoStack.append(doc)

doc.addItem(Circle())

undoStack.append(doc)

Now, our undo_stack has 3 distinct instances of Diagram. These aren't references to the same Diagram because we're using value semantics.

In an app, this could enable a history feature that gives us a list of all our states. We can easily go back and forth just by indexing into the undo_stack.

In fact, Adobe Photoshop uses value semantics to implement their history feature. Every action results in a new doc instance, and this is efficient because of copy-on-write.

Summary

- Reference semantics and unexpected mutation can lead to bugs

- Value semantics solve these problems by giving you the expressiveness of mutability and the safety of immutability

Twitter

Twitter

GitHub

GitHub

www.linkedin.com

www.linkedin.com